Where Do California's High Electricity Prices Come From?

The state of California pays the second highest rate for electricity in the country: 22.33¢ per kilowatt-hour (kwh) in 2022. Only the isolated island state of Hawaii pays more according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA).

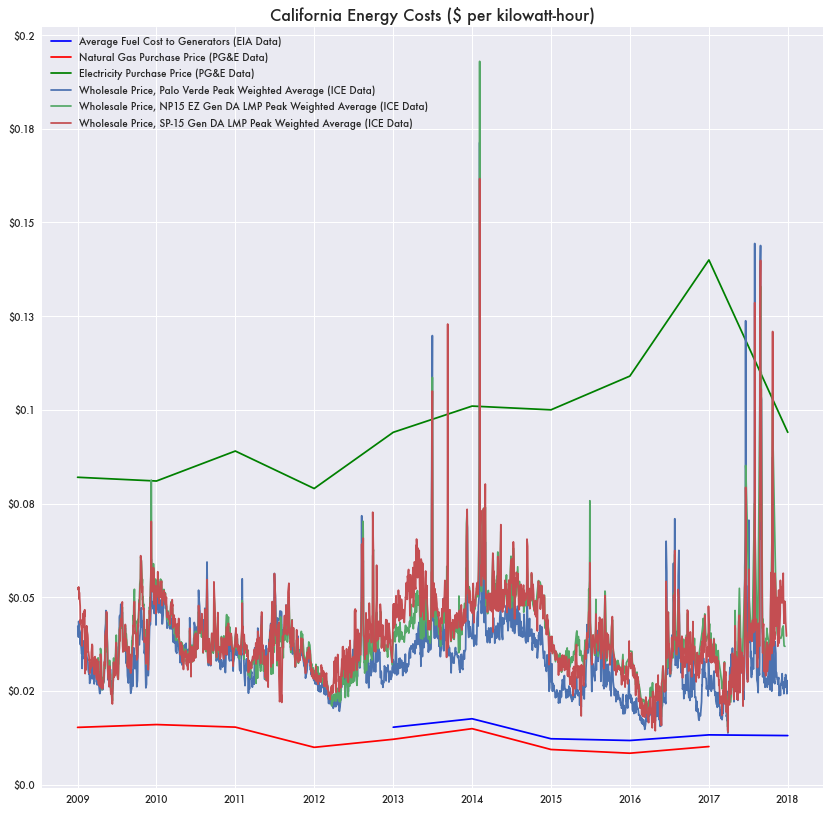

Average retail prices have increased year over year and are now higher than what they were at the peak of the 2001 Enron energy crisis (around 15¢/kwh). Prices keep increasing above inflation despite the relatively low price for natural gas driven by the shale boom.

Part of those increasing costs are connected to the state’s environmental agenda. California’s aggressive push towards a zero carbon economy means large mandates for low carbon energy like solar, wind, and hydroelectric—accounting for 54 percent of state electricity generation. Power generation from coal was already fazed out years ago.

Critics have regularly highlighted the high costs of reliance on intermittent sources of electricity like solar and wind; they cease to operate when the sun doesn’t shine, the wind doesn’t blow, and there can be large financial burdens to handle that intermittency. But the financial burden of renewables on California may not come from their operating costs.

Other states that lean heavily on wind and solar haven’t seen such price spikes. Right next door is Nevada which didn’t deregulate their energy grid. The silver state now consistently relies on solar generation. Over 30 percent comes from non-hydroelectric renewable sources according to EIA data—about the same amount as California. Large swaths of the midwest use wind for baseload generation without much concern or large financial burden on customers.

Yet California’s main utility, Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) now pays over 10¢/kwh on average to obtain energy before providing it to customers. In 2017 it was 14¢/kwh. Compare that to Nevada where it’s around 4¢ to 5¢ per kwh according to annual reports from Nevada Power.

California’s high prices appear independent of the changing costs of natural gas or wholesale energy markets. The weighted average wholesale costs at California hubs like NP15, SP15, and Palo Verde rarely peak above 5¢ per kilowatt-hour. And those hub prices are not significantly different from other wholesale trading hubs across the country.

Depending on how they are measured, solar and wind are ostensibly cheaper than, or equivalent to, nuclear, natural gas, and coal in terms of levelized cost of energy (LCOE). That’s even before tax breaks and subsidies are factored in.

But it seems like renewables are the problem. PG&E’s annual report data doesn’t break down the cost of energy purchases based on energy source, but renewables represent around 70 to 75 percent of third-party purchase agreements, most of which is solar.

The 2017 PG&E annual report notes that prices would continue to rise “to procure renewable energy to meet the higher targets established by California SB 350 that became effective on January 1, 2016.”

Energy Generation Versus Energy Purchases

For renewable energy, PG&E has to buy from third parties as the company produces little of its own outside of large hydroelectric dams like Feather River Canyon. While 15 percent is from large hydroelectric generators, just 2 percent of total generation in 2022 is from non-hydroelectric renewable sources like wind, solar, and biofuels. Otherwise, most of its in-house generation capacity comes from nuclear (49 percent) and fossil fuels (18 percent), mainly natural gas.

Essentially, in-house generation is simply much, much cheaper. The cost of fuel for in-house generation is almost negligible at $473 million in 2022.

While that does not include costs for plant operation, compare that to the price of net purchased power, which varies from $2.9 billion to $5.3 billion a year despite only providing around 41 percent of generated capacity.

And that is net purchased power—the amount spent to buy electricity minus sales of electricity to other providers. So ostensibly the market price paid for power may be even higher if outgoing electricity sales were removed from the equation.

CCAs and Deregulation

Complicating the matter is that PG&E now farms out a substantial amount of energy purchasing to other utilities known as Community Choice Aggregators (CCAs). As part of energy deregulation that began at the end of the 1990s, Californians now have the option to choose which company they buy their electricity from. PG&E still provides the distribution, but the CCA provides the power.

A number of the CCAs focus on providing a larger mix of renewables, sometimes up to 100 percent at prices competitive with PG&E.

With more customers choosing CCAs, it means PG&E provides less. As a result, the amount of electricity PG&E buys has declined by almost half since 2014 as prices have gone up.

Declining Nuclear Generation

California was set to shut its sole nuclear power plant—the Diablo Canyon power plant near San Luis Obispo—by 2025 as part of an agreement with energy groups to focus more on renewable energy. The San Onofre nuclear plant was shutdown in 2013.

But the planned shutdown of Diablo was averted in 2021 as numerous groups highlighted the risks to reliability and the potential for blackouts.

California Independent System Operator (CAISO)—the independent entity which oversees California’s energy markets—noted that the plant’s shutdown would put the grid at a “critical inflection point” from limited capacity.

Recent Data

PG&E annual reports have not listed average price or total amounts paid for purchased electricity in recent years, but there’s some indication that prices could be even higher.

Starting in 2020, wholesale prices along the West Coast, which were once regularly below 5¢/kwh, grew and would eventually spike as high as 30¢/kwh by early 2023, potentially from repercussions of the pandemic and how the Russia-Ukraine war affected oil and gas markets.