Discover more from Investigative Economics

What Stopped Lithium Production in 2010

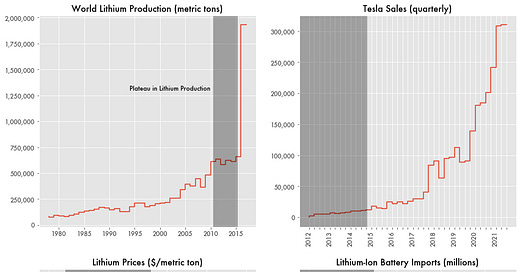

Around 2010 to 2015, global lithium production plateaued.

Demand for the main ingredient in lithium-ion batteries had been steadily growing over the previous five years as the technology became the de facto battery in the growing electric vehicle (EV) market as well as many portable electronics. Between 2010 and 2015, demand suddenly went from steady growth to constant, only to switch back to even greater exponential growth in 2017.

Anecdotal explanations for the stasis ascribed it to a lack of demand for electric vehicles. EVs were still relatively new at the time and consumers might be hesitant to purchase the higher priced vehicles while the technology was still in its infancy. Without the demand for EVs, lithium battery production stalled with it.

Lack of demand was cited by the battery startup Ener1 in its bankruptcy filings in 2011, and the company was lumped in with Solyndra by Mitt Romney as a sign of the failure of government’s flawed investments in green energy.

Additionally, a presentation by then-Secretary of Energy Steven Chu at a 2010 U.N. Climate Conference sparked skepticism that lithium-ion batteries were potentially a dead-end. But while Chu’s speech inspired some lithium skepticism, he also noted that large advancements in the technology were on their way.

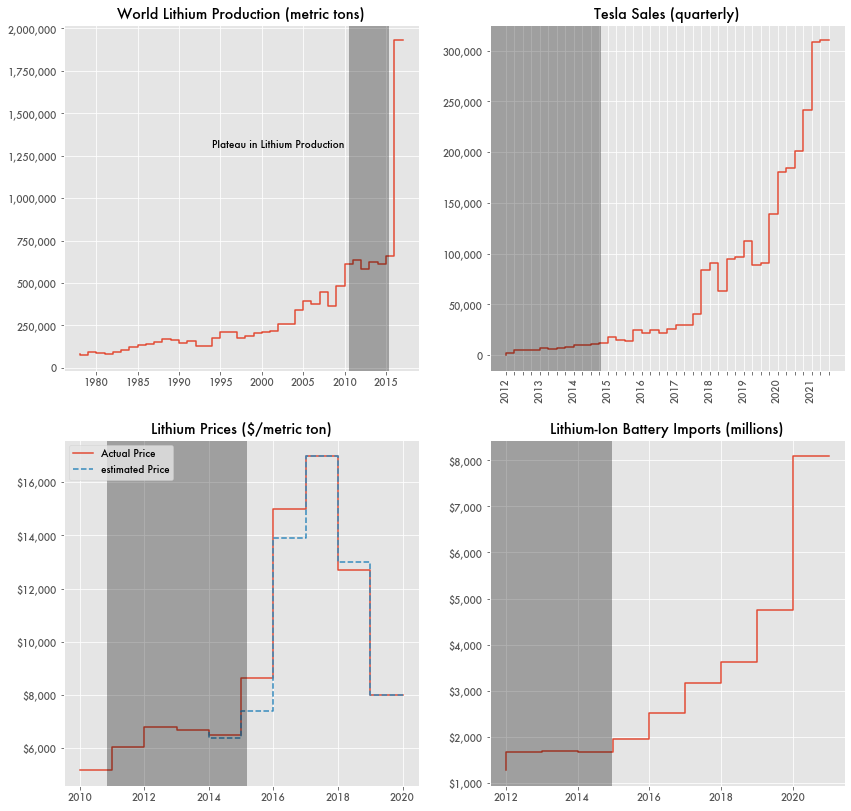

And in 2017, demand for lithium and lithium-ion batteries came back strong. Australia became a lithium-producing powerhouse and China followed suit.

While China's production dropped between 2013 and 2015, it came back online quickly. From 2000 to 2010, annual Chinese lithium production increased by 1,600 tons. Between 2017 and 2019, annual production increased by 4,000 tons.

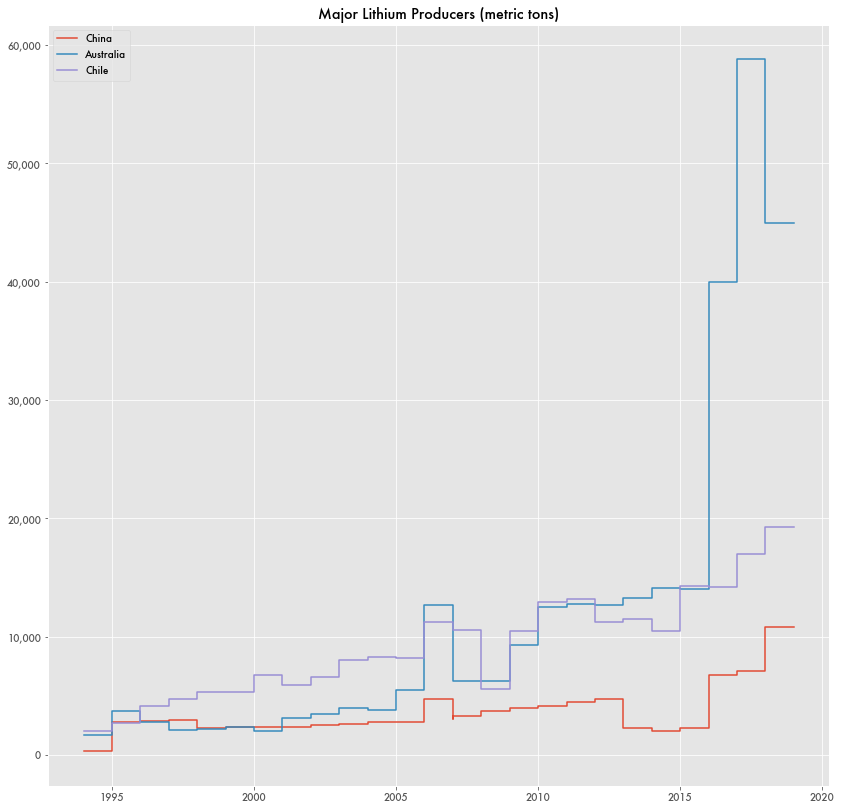

With the sharp rise in global production in 2017, lithium prices and EV car sales, like those of Tesla, jumped as well.

The flattening of lithium production was somewhat predicted by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), which believed global production would be relatively level through 2017 according to a 2013 report.

USGS's prescience on lithium demand implies that lack of consumer demand for EVs wasn't the driver of battery sales and production. Large improvements in lithium-ion battery technology were on the horizon and manufacturers were willing to wait.

In the same timeframe, performance of lithium-ion batteries jumped substantially in terms of electricity storage and these forthcoming performance improvements were known ahead of time by the Department of Energy.

Lithium battery research got a huge boost in 2009 as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. The Department of Energy funded $2.5 billion towards battery and EV manufacturing grants. Lithium battery technology figured prominently with about $940 million in grants.

In 2014, a Silicon Valley company, Amprius, developed a lithium-ion battery that stored 20 percent more power than previous models—a significant improvement. Amprius was founded by Yi Cui, a highly recognized materials science researcher who has worked with Steven Chu.

Ener1 Bankruptcy

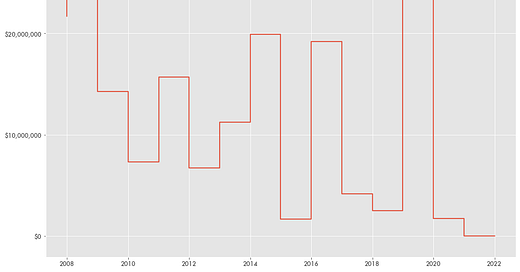

The descriptions of lower demand for EVs was not solely anecdotal. For the lithium-ion battery manufacturer Ener1, which entered bankruptcy in 2011, one of the major contributing factors to their bankruptcy was a “decline in demand for EVs.” The company also attributed the bankruptcy to “volatility in the debt and equity markets” and the loss of a major customer: Norwegian electric vehicle manufacturer Think Global. Think Global fell into bankruptcy, which was a double-edged loss for Ener1 as Ener1 was also a large investor in Think Global.

Ener1's bankruptcy was notable because it was one of a number of renewable energy startups that received large Department of Energy loans only to collapse soon after. In one of the 2012 presidential debates with Barack Obama, then-presidential candidate Mitt Romney highlighted Ener1, along with Solyndra and Tesla, as green businesses that the government picked to be “losers.”

But don’t forget, you put $90 billion, like 50 years’ worth of breaks, into – into solar and wind, to Solyndra and Fisker and Tesla and Ener1. I mean, I had a friend who said you don’t just pick the winners and losers, you pick the losers, all right? So this – this is not – this is not the kind of policy you want to have if you want to get America energy secure.

While Ener1 entered bankruptcy, it eventually received financing to sustain itself and continued on as a private company with a manufacturing hub in Indiana. Solyndra didn’t fare as well.

Unwarranted Skepticism of Lithium-Ion Technology

At the time around the flattening of lithium production, there were also some theories that lithium-ion batteries just weren't the technology that would make EV efficiency possible. Following a talk by then-Energy Secretary Chu at the 2010 United Nations Climate Change Conference, John Peterson, a writer for Alt Energy Stocks, believed Chu was inferring that lithium-ion batteries were a “dead-end” for electric drive technology and that investors in battery tech companies like Ener1 should be concerned.

This belief was repeated in a blog by Dexter Johnson from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE)—the world’s largest technical professional organization.

Although Chu never said that lithium-ion batteries are a dead-end but simply noted that lithium batteries would need to have 6-7 times higher storage capacity to be competitive with combustion engines. Chu added that current batteries were improving quickly.

Meanwhile the batteries, the ones we have now, will drop by a factor of two within a couple of years and they're gonna get better. But if you get to this point, then it just becomes something that's automatic and I think the public will really go for that.

Chu's presentation stated that EV batteries would need a storage density of 1,000 Wh/L to be competitive with gasoline engines. Yet, current lithium-ion batteries only have a storage density of around 250-670 Wh/L. Despite the lower storage capacity below Chu’s standard, numerous EVs and hybrids have still become competitive with combustion engines.

The IEEE version of the story also didn't believe that Tesla cars could travel 200 miles on a single charge—current Teslas can go around 300 miles per charge—and that maybe lithium-ion batteries are only best for personal gadgets:

"...we may need to look somewhere else if we want to get serious about replacing the internal combustion engine in our vehicles."

Subscribe to Investigative Economics

Investigative and data-driven independent news combining forensic statistics and economics