The Sudden Halt in Lung Transplants for Cystic Fibrosis Patients

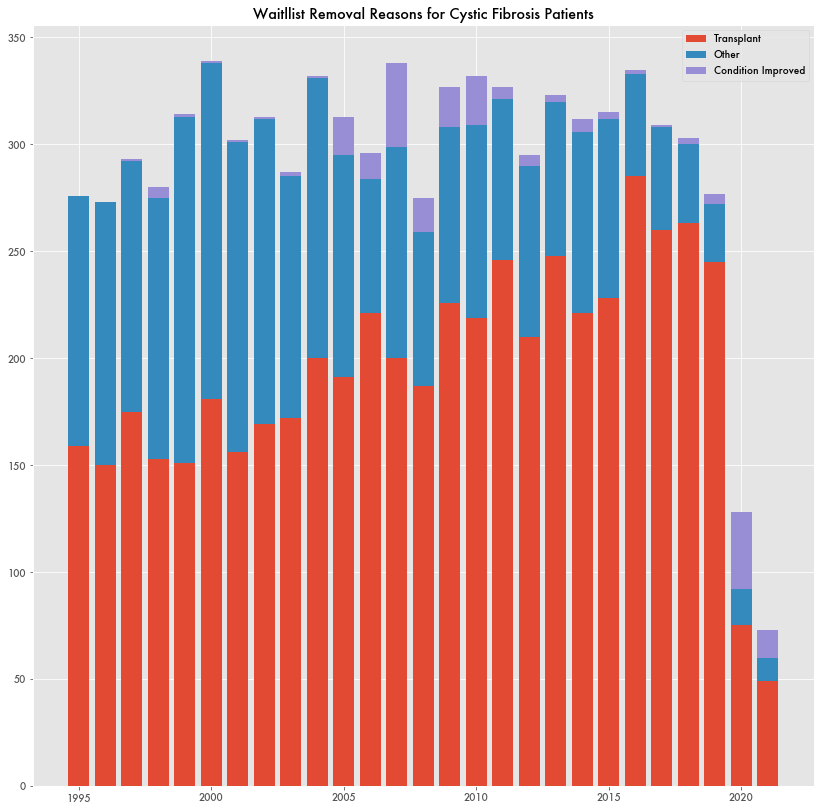

Since 2000, there have been 237 to 350 lung transplants a year for patients suffering from cystic fibrosis. In 2020, there were 78 based on data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) of the Health Resources and Service Administration (HRSA). HRSA is a subagency of the Department of Health and Human Resources (HHS).

The sudden drop-off doesn't appear related to a lack of available organs or pandemic limitations. Transplants for every other lung condition continue unabated despite pandemic limitations.

The number of new cystic fibrosis patients added to the waiting list for a lung transplant in 2020 was 1/4th what it was the year prior. The same goes for those removed from the waiting list either for lack of need or other reason.

It's as if the whole process for cystic fibrosis-related transplants came to a halt.

The change in transplants was highlighted by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) during a recent National Institutes of Health (NIH) presentation about cystic fibrosis treatments. In 2019, the year prior to the change in transplants, is when Vertex Pharmaceuticals released Trikafta—regularly described as a “groundbreaking treatment” for cystic fibrosis. The implication in the NIH presentation was that the treatment was already leading to fewer lung transplants.

What might seem like a resounding response to the treatment—fewer transplants—may simply be patients avoiding surgery in anticipation of the new treatment. A 2020 report from the U.K. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation noted a drop in transplants there as well, going from 45-50 a year to 12 in 2020, but that the drug had only been available for those on a managed access agreement, and a U.K.-wide rollout was expected at the end of the year.

And there's no definitive sign that patients are having full recoveries. While 2020 saw a significant number of patients removed from the waitlist because of their improved condition, 36, it's not totally anomalous as prior years have seen similar changes. And the number of patients removed from the waitlist for improved conditions in 2021 was only 13—not particularly significant.

It may be too early to tell if the treatment is leading to reduced mortality. Trikafta was approved in June of 2021 but already Centers for Disease Control (CDC) mortality data shows fewer deaths in 2020 than the year before, going from 372 to 269. Although deaths due to chronic lower respiratory illnesses, which includes cystic fibrosis among other respiratory conditions, have increased.

Another change around that time is that OPTN announced plans to update its process for determining lung allocation scores (LAS)—the metric it uses to determine who is available for a lung transplant—to incorporate more recent data. While the proposal was announced in 2020, the changes won't be incorporated until 2023.

Trikafta Hype

The new cystic fibrosis treatment has garnered a lot of attention, with a Washington Post story describing it as potentially turning a deadly disease into a manageable condition. According to the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) announcement on its approval, Trikafta, or Kaftrio in the U.K., is the first to target the major F508del mutation that affects 90 percent of sufferers—although other drugs developed by Vertex like Orkambi and Symdeko have been approved that also treat those with the F508del mutation.

It's a triple combination therapy that builds off of the success of ivacaftor—a drug developed by Vertex to treat cystic fibrosis suffers with a different mutation—G551D—that only affects around 5 percent of sufferers. Ivakaftor was approved by the FDA in 2012.

While the success of the drug is being applauded, with 2021 Q4 sales at over $2 billion for one of the most expensive drugs available (Trikafta can sometimes cost over $300,000/year), Vertex also has a history of overhyping its results. Previous combination therapies for cystic fibrosis based on ivakaftor—which were also heavily promoted and received the FDA's breakthrough therapy status, orphan drug status, and priority review—were not as successful.

Symdeko, which uses tezacaftor and is intended for those with the F508del mutation, had a 6.8 percent improvement over baseline for FEV1—forced expiratory volume of air in 1 second, a common measurement of breathing capacity and cystic fibrosis status. It was something noticeable but not a clinical breakthrough.

Clinical trials for Orkambi—lumacaftor with ivacaftor for the F508del mutation—showed little benefit with lumacaftor alone showing “no clinical benefit.”

Previously, Orkambi had shown a 10 percent benefit during phase II of a clinical trial, and when the news hit, Vertex’s stock jumped 55 percent in volatile trading. But the successful news was retracted. The results were incorrect. Instead the drug's efficacy was meager. The FDA would still approve it 3 years later as a “breakthrough therapy” with an orphan drug designation.

The inaccurate results were blamed on an outside vendor. But during the brief peak, insiders and hedge funds sold off stock in the millions. Pension funds that bought in took a hit as the stock price came down.

Usually such activity would flag an insider trading investigation, but the SEC didn't budge. The trades were made through 10b5-1 retirement plans which allow for trading during the release of market moving news as long as the trades are planned out in advance. Trading this way has long been flagged as a gaping loophole that enables insider trading just as long as the traders plan out their market moving news in advance.

This wasn't the only time Vertex was accused of misleading markets. Vertex was previously investigated by the SEC for withholding the toxicity results of a rheumatoid arthritis medication, VX-145, as a way to enable insiders to sell before the stock dropped.

By avoiding financial collapse following the failure of VX-145 and an attempt at a hepatitis C treatment, Vertex had enough capital to buy out Aurora Biosciences—a small biotech firm in California founded by scientists at University of California at San Diego—which had made great strides in developing a treatment for cystic fibrosis, which would lead to ivacaftor.