The Steady Decline in Hail

Fewer frozen pellets are falling from the sky

At one point in 2008, there were almost 18,000 reported hail events (17,768) based on reported storm event data from NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). Ten years later, in 2018, there were 10,000 fewer (7,863).

As a percentage of all reported storm events, it went from around 25 to 29 percent a decade ago, down to 12.5 percent in 2018. It still remains the second most common reported storm type after thunderstorm wind.

Most of the decline in reported events came from Plains states like Kansas and Oklahoma, as well as Texas. In a decade, the number of hail storms in both Oklahoma and Kansas has been cut in half.

While the number of hailstorms has gone down, they are still causing plenty of damage. In 2016, over $3.5 billion in assessed damage came from hail, the highest on record in the data.

Other events have since taken the place of hail, and 2019 listed the third highest total number of storms in the data's 20-year history, largely due to increased incidents of thunderstorm wind—the most common storm type listed for any year—and floods.

In the last two years of data, there were 64 percent more floods reported (9,482) than in the previous 18 years on average.

The data is a collection of reports from a variety of sources, including trained sources, police, and newspapers among others. Certain years have had inordinately high numbers of storms, such as 2011, 2008, and 2019, with no single area standing out. Reporting in general has increased dramatically since data collection began in 2000, with about 10,000 more events recorded on average per year since then (20 percent increase). Most incidents occur in Western and Plains states like Kansas, Wyoming, Iowa, and Colorado.

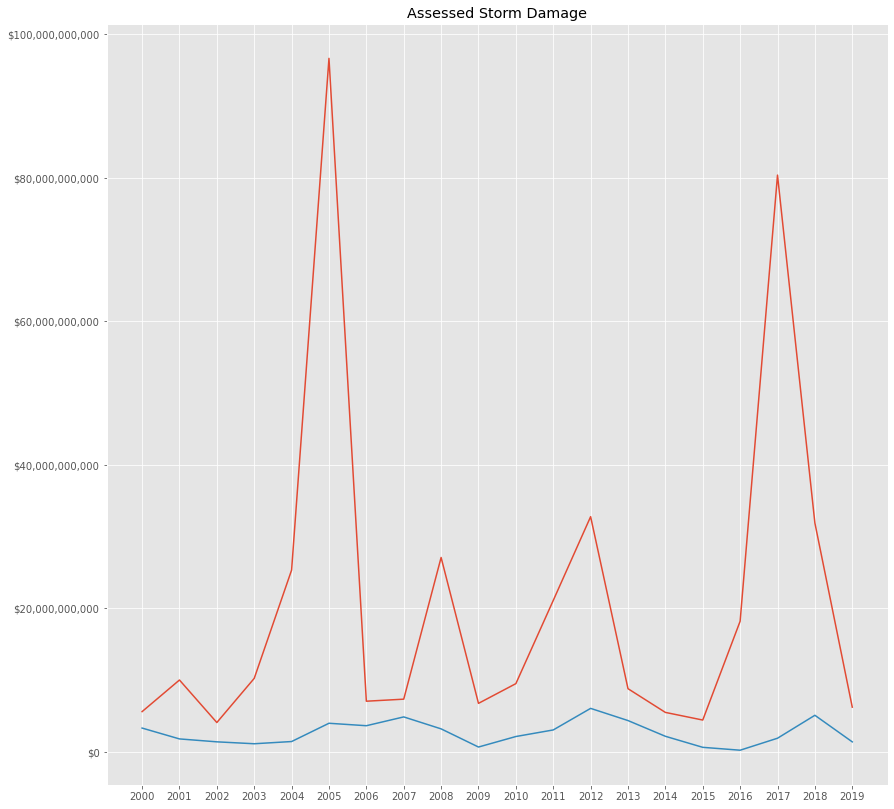

Besides the quantity of reported storms, the total reported damage appears to come in four-year cycles, similar to that of El Niño weather cycles. The years 2005, 2008, 2012, and 2017 were all heavy property damage years, although those years don't align with significant El Niño years.

While hail and wind account for the most common storms, it is floods, hurricanes, tidal surges, and tornadoes that cause the most damage. And the locations that incur the most assessed damage are the obvious ones: New Orleans after Katrina (2005), California wildfires (2018), Texas floods (2017), New Jersey after Sandy (2012).

NFIP Reform

Those reported spikes in damage also correlate to the spikes in flood insurance claims in the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP).

Through FEMA, the NFIP provides subsidized flood insurance and also requires flood insurance for all floodplain dwellings to receive a federally-backed mortgage. But not all homeowners required to have flood insurance have it. Estimates of NYC properties put the number between 61 to 73 percent paid for flood insurance when required.

The program was substantially revised in 2012 under the Biggert-Waters Act as the program put the Treasury $24 billion in debt following major hurricanes like Katrina, Sandy, and Rita. The program has a $30 billion limit set in law.

Before the amendment, the program's subsidized rates were pricing the insurance far below market rates. Certain properties were experiencing repeated losses not reflected in their premiums. Flood zones had changed over the years changing low risk areas into higher risk. The act also changed major components of the program, including flood maps and floodplain management. Since the changes, about half a million fewer NFIP policies are issued each year.

NFIP was amended again in 2014 through the Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act, delaying the increase in subsidies. As of 2021, the program is still $20 billion in debt.