The Federal Student Loan Portfolio is Hemorrhaging Capital

As part of the legislation related to the Affordable Care Act of 2010, the Federal government took over providing the vast majority of student loans.

Previously, the federal government helped underwrite low interest loans from private banks and other lenders. Now, the government lends directly to students through the Federal Direct Loan Program.

Cutting out the private lender middleman was supposed to save taxpayers on the order of $68 billion, but instead the government took over a portfolio of student loans with a massive default rate that was set to burst and keeps losing money year over year as tuitions continue to rise.

In 2015 the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) revised their estimates of the total amount of outstanding debt to be 30 percent higher than anticipated.

A 2022 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report noted that the Department of Education originally estimated that the 1997-2021 portfolio would generate $114 billion in income, but instead it was going to cost $197 billion—a $311 billion difference. Every year it has been in operation, the program has lost money with one exception, 2012.

The largest reason for the $102 billion restatement was due to costs from the COVID pandemic and the pause on student loan payments. It also mentions the difficulty in estimating payments from income-driven repayment plans—where borrowers only pay based on their income. Estimating repayment for those plans is more complicated and the estimates are less accurate.

But even before the pandemic, the portfolio was growing out of control. It topped $1.8 trillion before 2020 (in adjusted 2024 dollars) according to Department of Education data.

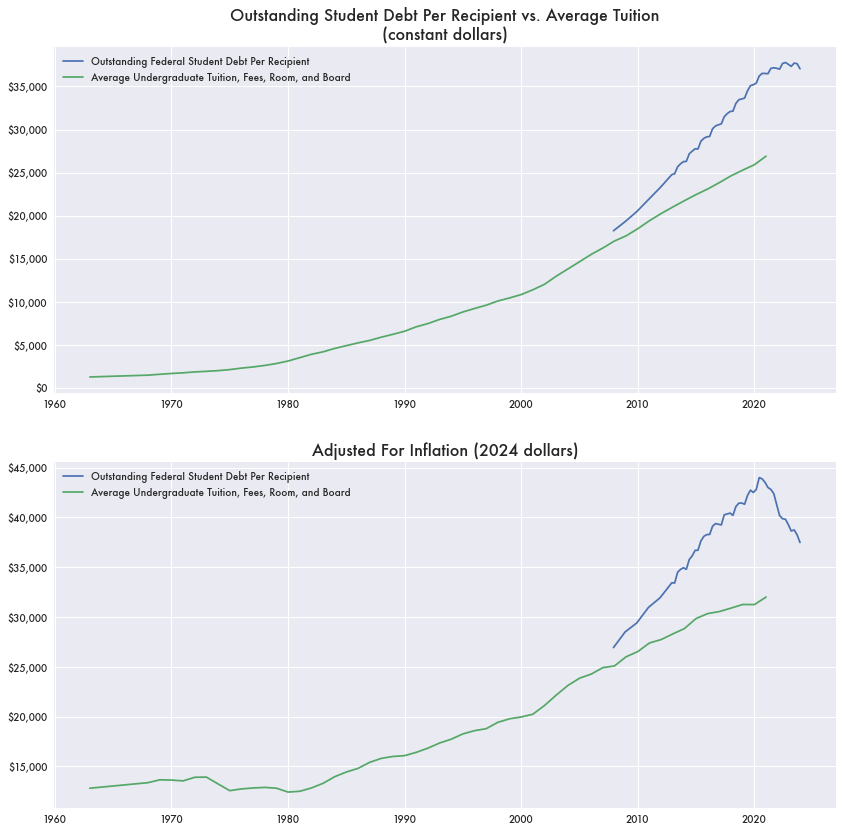

Debt Growing Faster Than Tuition

Some of that is due to the growing cost of tuition, which has risen year over year going back to the early eighties. But the outstanding student debt per recipient has risen even faster.

Tuition and debt are not necessarily equivalent: many students don’t pay the full tuition amount and many don’t need room and board. But they would ostensibly rise at a similar rate since student debt is based on some factor of tuition and room costs.

Between 2016 and 2017 outstanding debt increased by $74.7 billion while the total number of recipients barely increased by only 300,000.

Together, the additional new student loan debt per new recipient that year was an incredible $250,000. The prior year it was less than half that: $114,000.

Such a quickly growing rate of debt implies the growth is not coming from tuition but from growing interest on the whole portfolio.

Federal Takeover Stopped Growing Default Rates

One criticism of the federal takeover of the student loan program was that it was leading to a much higher default rate, but the opposite is true.

Two-year cohort defaults for all institutions (e.g. public, private, and others) would collapse just a couple of years after federal takeover. Prior to the takeover, default rates were skyrocketing and the burden of defaults was falling on private lenders.

By 2011, the student loan default rate was almost 14 percent—not too far off from some subprime default rates during the foreclosure crisis. Once the Feds took over the student loan portfolio, that rate would drop to almost 2 percent in 2019, essentially preventing the student loan bubble from bursting.

But with the new loan programs offered through the Department of Education, like income-driven repayment programs and other variations on loan forgiveness, it made paying down student loans less necessary for certain populations. If the borrower made no income, they didn’t need to make payments and therefore weren’t defaulting.

While those income-driven repayment plan loans may not be defaulting, their loans are still on the federal government’s books, potentially one of the larger drivers of the growing student debt balloon and declining default rates.

Enabling Tuition Increases

While the federal takeover of student loans helped prevent the bubble from bursting, federal grants for education were previously accused of subsidizing rising tuitions, going back decades.

In 1987, then-secretary of the Department of Education William Bennett argued that, “increases in financial aid in recent years have enabled colleges and universities blithely to raise their tuitions, confident that Federal loan subsidies would help cushion the increase,” otherwise known as the Bennett Hypothesis.

And federal grants for postsecondary education have largely followed the growth in tuition (Pearson correlation: .9177).

But it’s difficult to determine if federal grants enable tuition hikes, or if it’s the other way around: that tuition hikes force federal grants to rise to help students pay for school.

While the total budget for federal grants, mainly in the form of Pell grants, is a substantial $30 billion a year, it’s relatively small compared to the full student loan portfolio size. The maximum Pell grant is $7,395, while the average undergraduate tuition is now over $25,000 a year.

The student debt portfolio now increases by around $100 billion a year, while the largest yearly increase in Pell grants was a mere $19 billion.

Article is very clear and appreciate the information.

This in fact could likely be proved through detailed economic analysis.

Also, the student loan figures could be shown starting in 2000, where it looks like they rose exponentially from a stable base. Thanks for your analysis Llewelyn!