Military Coup and Textile Labor Tumult Preceded Honduran Migrant Influx

Over the last ten years Mexican immigration to the United States has been declining as fewer citizens attempt to cross the border.

But since 2010, there has been a different influx from Central America’s Northern Triangle—Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala.

That growth is regularly attributed to instability and criminal gangs in the region as those countries struggle with the world’s highest murder rates. Yet political and economic turmoil, particularly in Honduras around 2009, also played a part.

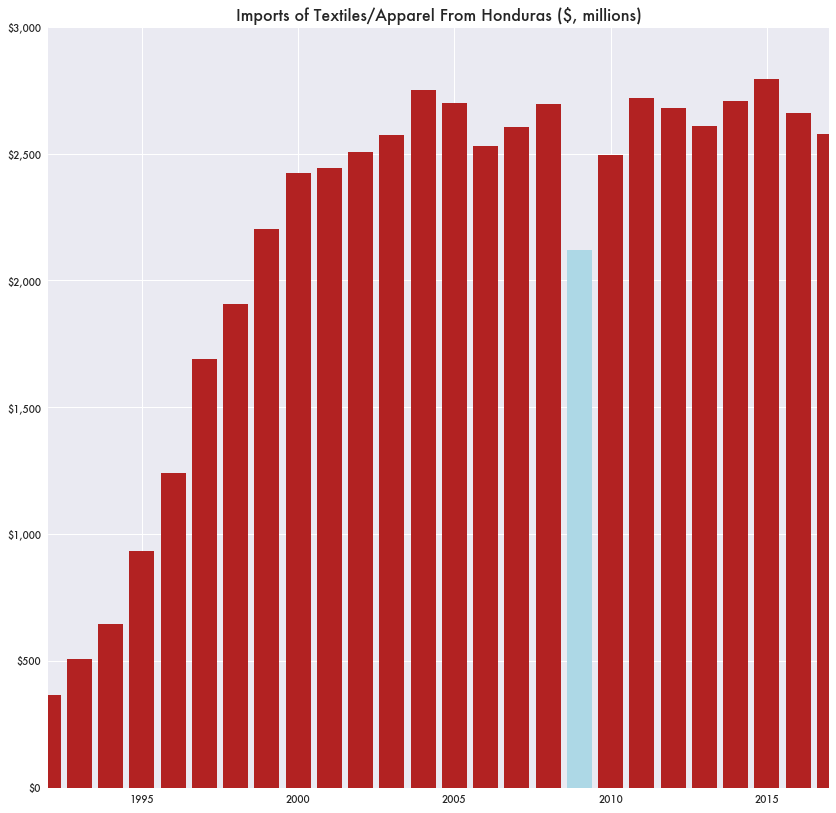

That year Honduras saw numerous labor disputes in the textile industry, a large drop in textile exports to the U.S., as well as a coup tacitly supported by the Clinton State Department.

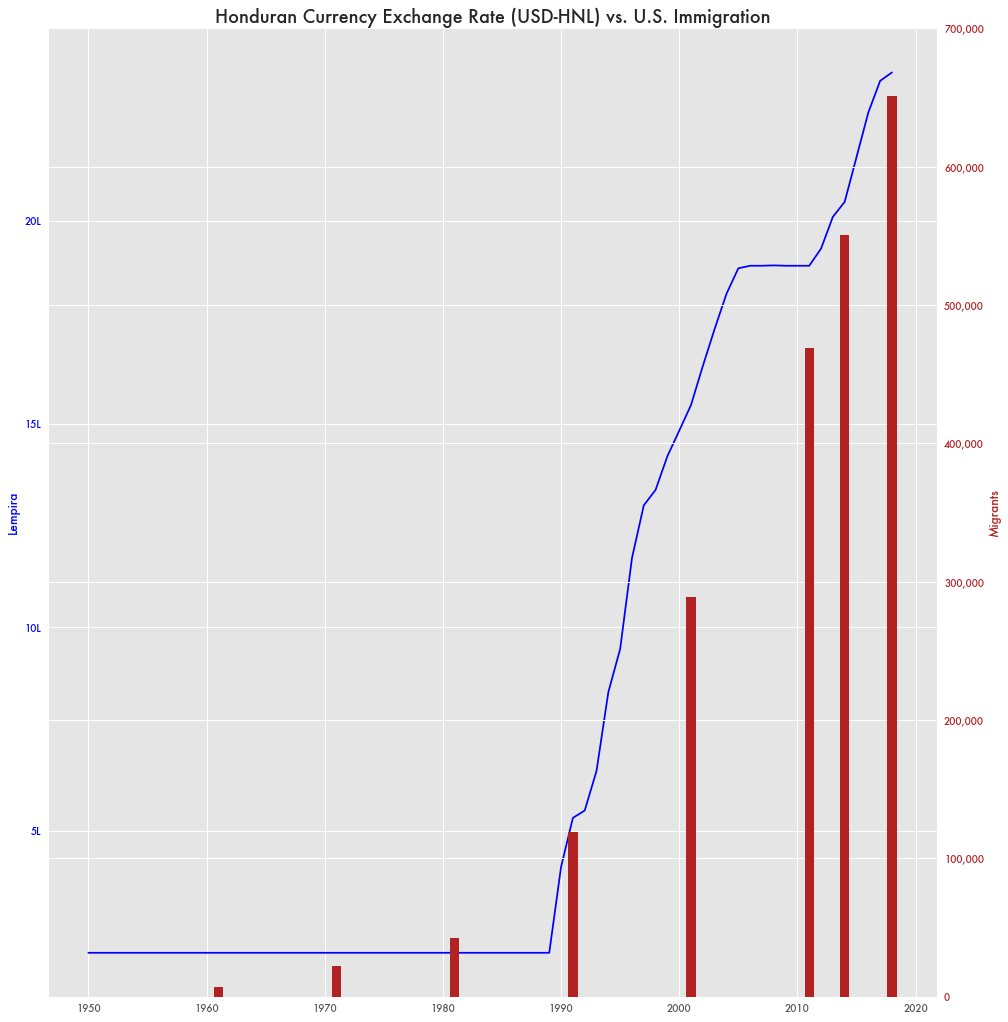

With the new Honduran president came a massive devaluation of their currency: the Lempira. The currency devaluation and subsequent growth in immigration led to a 50 percent increase in remittances—payments back to a foreign resident’s home country—as well as a spike in asylum requests, ostensibly related to the high crime and murder rate.

Yet while reported murder rates are high, the statistics are inconsistent with reported death rates and could be misleading.

Labor Disputes Under Zelaya

Honduras is home to a large textile industry for international brands, like Russell Athletics, which produces clothes under its own label and for other major labels like Nike.

In 2009, numerous labor disputes broke out and Russell Athletics closed a plant employing 1,800 people. They declined to pay severances after many of the employees unionized and entered into a contract dispute with management.

Potentially because of the factory closing, textile imports from Honduras to the U.S. dropped 20 percent in 2009.

Military Coup

At the time Honduras was governed by president Manual Zelaya, who was elected as a liberal 2005 but would shift to a more leftist Bolivarianism approach during his tenure.

In 2010 following the textile labor disputes, Zelaya would be deposed in a military coup following a scandal over Constitutional rule changes.

U.S. law requires that military coups immediately trigger a denouncement and cessation of all foreign aid to the country.

But then-Secretary of State Clinton never denounced the coup, and State department communications released by Wikileaks indicated that she didn’t want to denounce it. Instead, Clinton supported the incoming president, Roberto Micheletti.

Clinton’s Textile Base

Clinton received large donations to both her presidential election and the nonprofit Clinton Foundation around the same time by large companies importing textiles from Honduras.

That includes between $2 to $10 million from Wal-Mart and $500,000 to $1 million from Nike to the Clinton Foundation. Apparel and department stores gave a combined $628,305 to Clinton’s presidential campaign in 2016, much more than Trump received from the industry according to a story in WWD.

Devalued Currency Came With New Administration

With the new administration following the coup, the incoming president swiftly devalued the Lempira.

For many years, the Lempira was fixed with the American dollar through most of the 1980s at 2-to-1, but it was substantially devalued beginning in 1989. By 2004 the ratio was over 18-to-1.

Under Zelaya’s reign, the Lempira stayed fixed, but with the coup it was yet again devalued to almost a 24-to-1 ratio.

Immigration Parallels Currency Devaluation

Similarly, as the Honduran currency stayed fixed relative to the dollar, so did immigration to the U.S.

Before 1981, less than 43,000 migrants from Honduras entered the U.S. per year according to numbers from the World Bank. By 1990, it was over 120,000. By 2000, it was almost 289,000. And since 2010 it increased 39 percent to 610,000 migrants per year in 2017.

Remittances Follow Immigration

Money sent from the U.S. back to Honduras has also followed suit, going from $2.3 billion in 2010 to $3.8 billion in 2017, a 64 percent jump.

An analysis by the Pew Research Center shows that all three countries are in the top ten for remittances, with a combined total of over $14 billion in 2016.

Asylum Requests Spike

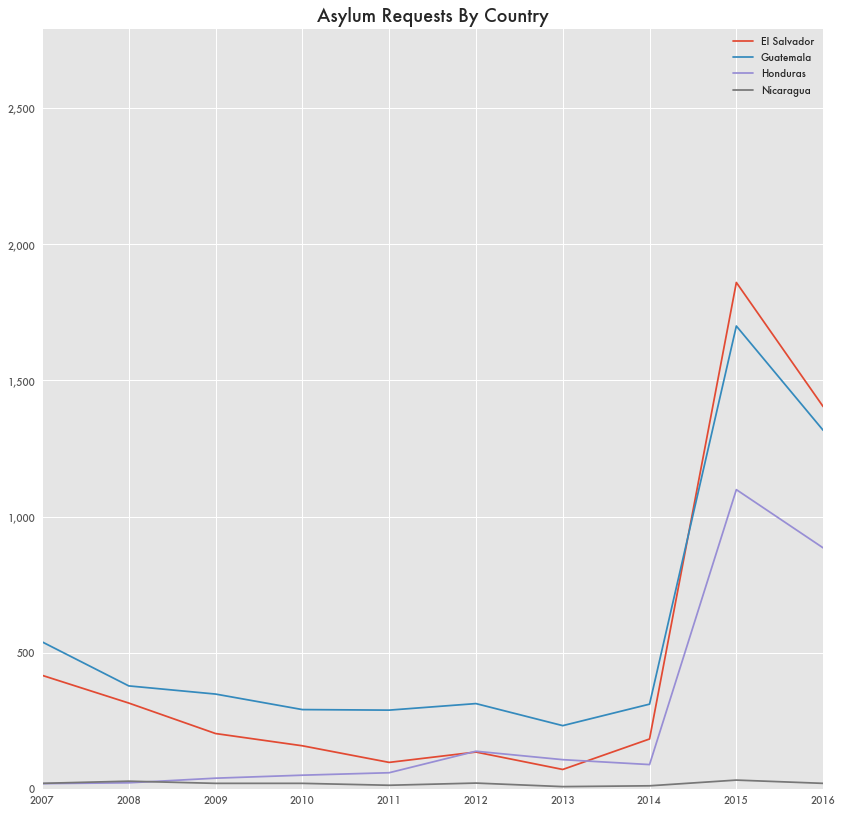

The Northern Triangle has seen its fair share of instability and violence, like that surrounding the civil war in El Salvador in the 1980s, and El Salvador has always had a substantially high murder rate.

But asylum requests from various countries had tended to be low, with less than 600 requests per year.

That all changed in 2015 when there were a thousand more asylum seekers from Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, but not other Central American countries like Nicaragua.

The Northern Triangle now accounts for over 30 percent of all asylum seekers to the U.S.

Large Discrepancy in Mortality Statistics

The North Triangle has had the highest murder rates in the world in recent years following political and economic tumult according to numbers from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

But the vast number of reported homicides do not appear to have affected related statistics on the respective countries’ overall rates of death.

Mortality rates for those countries have been on a downward trend over the last fifty years and is currently similar to other nearby countries not experiencing a sudden spike in violence, like Costa Rica and Nicaragua.

For 2016, El Salvador’s homicide rate (82.54 per 100,000 inhabitants) is over ten times that of Nicaragua (7.37). There were days in 2015 with over 20 murders.

For Honduras, the homicide rate almost doubled between 2006 and 2010. But the death rate went down over the same time period. Based on estimated population of 7.5 million (2006) and 7.6 million (2010), that would mean approximately 2,665 more homicides in 2010 than 2006 that didn’t affect the overall death rate.

Despite the ongoing slaughter, both countries rank relatively low in the CIA’s mortality rate statistics. El Salvador is 176th, and Honduras is 180th out of 230 countries.