Measles Deaths Disappeared Before the Vaccine

Measles, or rubeola, is a highly contagious disease that causes fevers and spots and was associated with 5,087 deaths in the U.S. in 1907. A 1954 outbreak in Boston led researchers to isolate the disease, culture it, and eventually develop a vaccine that would be authorized in 1961 and widely distributed in the U.S. in 1963.

According to a 2003 Centers for Disease Control (CDC) paper on vaccine mandates and their success, Vaccination Mandates: The Public Health Imperative and Individual Rights, the annual 20th century morbidity for measles went from 503,282 to 81 by the year 2000—a 99.8 percent decrease.

The implication is that the introduction and widespread use of the measles vaccine led to that decline in morbidity.

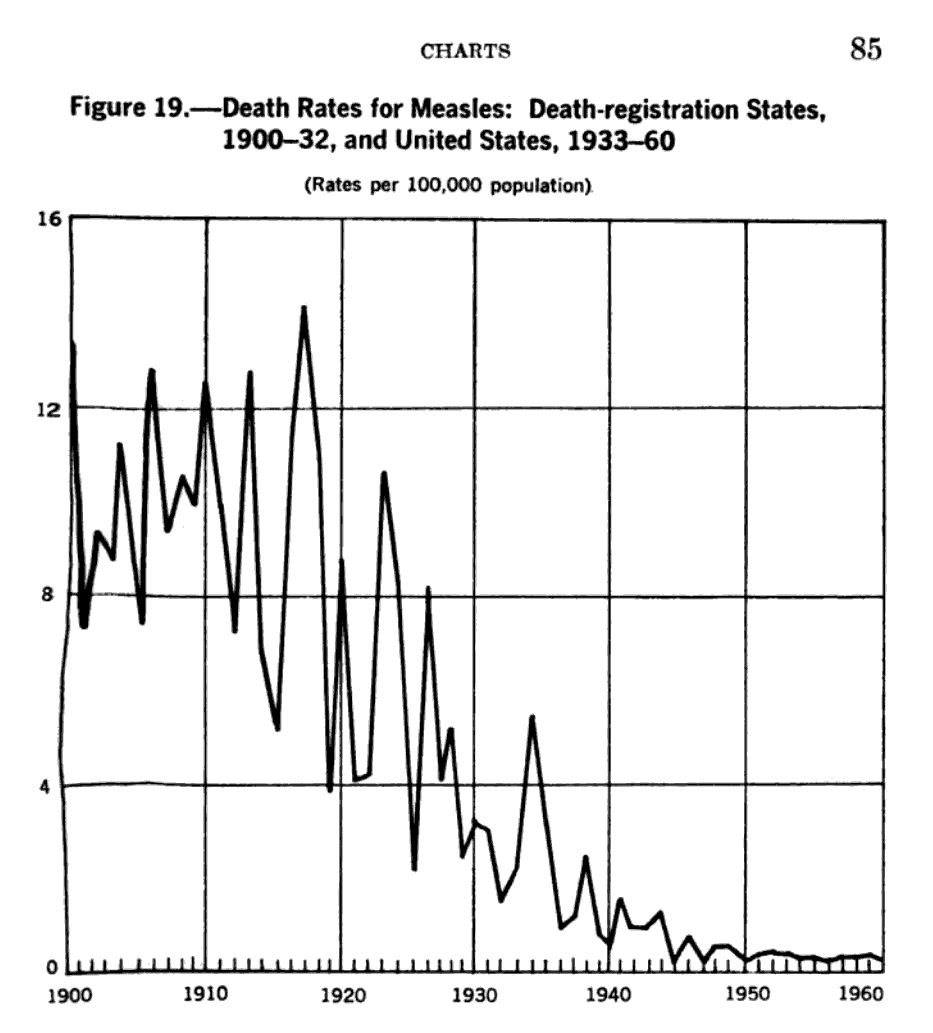

But deaths due to measles were in sharp decline years before a potential vaccine was discovered and certainly before it was widely distributed. In 1910, there were 12 deaths per 100,000 in the U.S. By 1959 it was .2 with only a total of 300 deaths according to a U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare vital statistics report.

Other Causes of Morbidity Decline

The World Health organization website details that general health improvements like better nutrition and the availability of antibiotics to help treat complications have likely helped the decline in measles deaths.

In general many diseases saw sharp declines around the early 20th century alongside improvements in quality of life, sanitation, and medicines. For example, the discovery of penicillin in 1928 and its development into an antibiotic treatment in 1939 would help treat a whole host of diseases, like syphilis, which effectively disappeared as a result.

Correction: A previous version of this story included some details about mumps and rubella that conflated morbidity with mortality. That section has been removed.

"But the 2003 CDC report states that 152,209 people die from mumps annually in the 20th century and 47,745 from rubella."

Table 13-1 which you post a picture of clearly states 'morbidity'. Morbidity refers to the number of cases of illness, 'mortality' means deaths. Table 13-1 states 152,209 per year were sick of mumps annually in the 3 years ahead of the vaccine licensure (not for the full 20th century, the footnote on this is directly at the bottom of the table you copied). It seems you may be confusing some vocabulary.

More broadly, preventing illness is still important. If you look at the measles in the United States this year, there have been 2012 cases, 'only' 3 deaths, but also 227 (11%) hospitalizations (https://www.cdc.gov/measles/data-research/index.html). If we went back to 500k cases a year, that would be 57k hospitalizations a year. Each hospitalization has an average cost of $14k (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/topics/hospitalization.htm), so this would cost the country about $800M in direct healthcare costs, and then you'd want to add in costs of lost wages for people who were sick, their caretakers, impact of missed schooling, worse care for people who need to wait longer because beds are taken up with measles, etc. to get the broader impact.