Housing Crash Redux: Collateralized Debt Obligations Came Back And Nothing Happened

Supposedly, collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) were at the heart of the subprime mortgage crisis. Complex derivatives turned a medium-sized problem into a massive one.

And it was various deregulatory maneuvers a few years prior, starting with the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) in 1999, that enabled the world of financial derivatives to flourish.

GLBA instantly eliminated the proverbial Chinese wall between commercial and investment banking that previously prevented banks from issuing securities that they could then bet against—something that harkened back to the failure of Citibank during the crash of 1929. Companies like Bear Stearns, whose collapse was possibly the first event during the 2007 crash, was heavily invested in CDOs.

With that deregulation came a wellspring of investment in CDOs. What was nonexistent would swell to a few hundred billion and eventually top out at almost $500 billion in 2007 before crashing during the financial crisis. Economists and investors like Paul Krugman and George Soros believed the instruments should be more regulated or banned altogether.

Banks could hand out shoddy subprime mortgages to those who wouldn’t be able to pay. Those mortgages would be wrapped into mortgage-backed securities (MBS). Those securities were then compiled into a CDO and sold to investors. Then the banks used credit default swaps to bet against those investments—effectively a bet on whether the debt would fail or not.

Maybe the best example of their abuse was the Goldman Sachs Abacus deal. With Abacus, Goldman Sachs created a synthetic CDO—a CDO that doesn’t actually own the underlying asset—on behalf of Paulson and Company, a hedge fund representing billionaire investors like John Paulson and George Soros. Paulson then bet against the CDO using a credit default swap. So many of the underlying mortgages defaulted that over $300 million was paid out on that credit default swap alone. In total, John Paulson’s bets’ against the housing market earned him $3 to $4 billion, possibly the largest single year payday in Wall Street history.

Goldman would eventually be fined $550 million for misleading investors about their role in the deal by not properly informing investors that they had compiled the securities in the CDO. Although Goldman defended its practice as the company lost $90 million of its own money invested in the CDO.

But the housing market has come back as if nothing happened. Home prices have surpassed what they were at the top of the 2007 market.

And with it has come renewed investment in CDOs. In 2017 almost $300 billion worth of CDOs were issued based on data from the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA)—not as much as the top of the pre-crash market but getting there. Daily trading volume by quantity is over ten times what it was ten years ago. By price, it’s twice what it was.

Yet if the prevalence of CDOs were a measure of shoddy mortgages, the repercussions have yet to be felt. There’s been no substantial collapse in the housing market despite rising interest rates and other pandemic events.

Bear Stearns supposedly collapsed because of how heavily they leaned on CDOs and subprime lending—around 69 percent of their portfolio or $18.3 billion worth based on a published report by J.P Morgan. In 1997 they along with First Union were the first to offer a security based on Community Reinvestment Act loans.

J.P. Morgan would go on to buy Bear Stearns out at a fraction of what it was worth a few months prior when no other institution would lend them money at the time.

The story of Bear Stearns’ collapse didn’t make a lot of sense. How could a financial company with so much invested in CDOs not see the risk? With the collapse of the company’s stock, executives would lose out on billions. Although a 2009 paper from Harvard researchers estimates that executives had already made billions during the few years before.

Differences From 2007

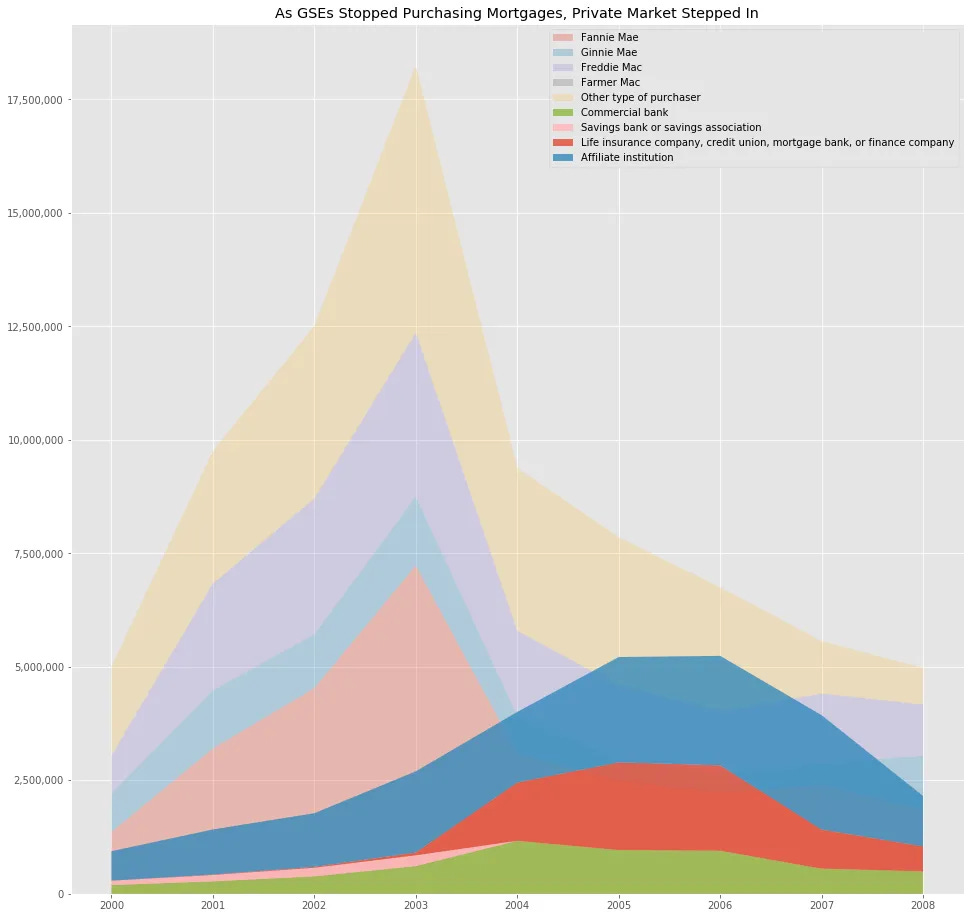

One difference between the financial crisis and today is that the market for commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) no longer exists—securities issued by private entities like banks rather than government entities like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac who have access to individual tax documentation of applicants.

Commercial brokers stepped in as interest rates started rising around 2004. The higher interest rate meant higher mortgage rates and higher risk, particularly for adjustable-rate mortgages. In October 2005, it was reported that 61% of recently originated loans in California were interest-only.

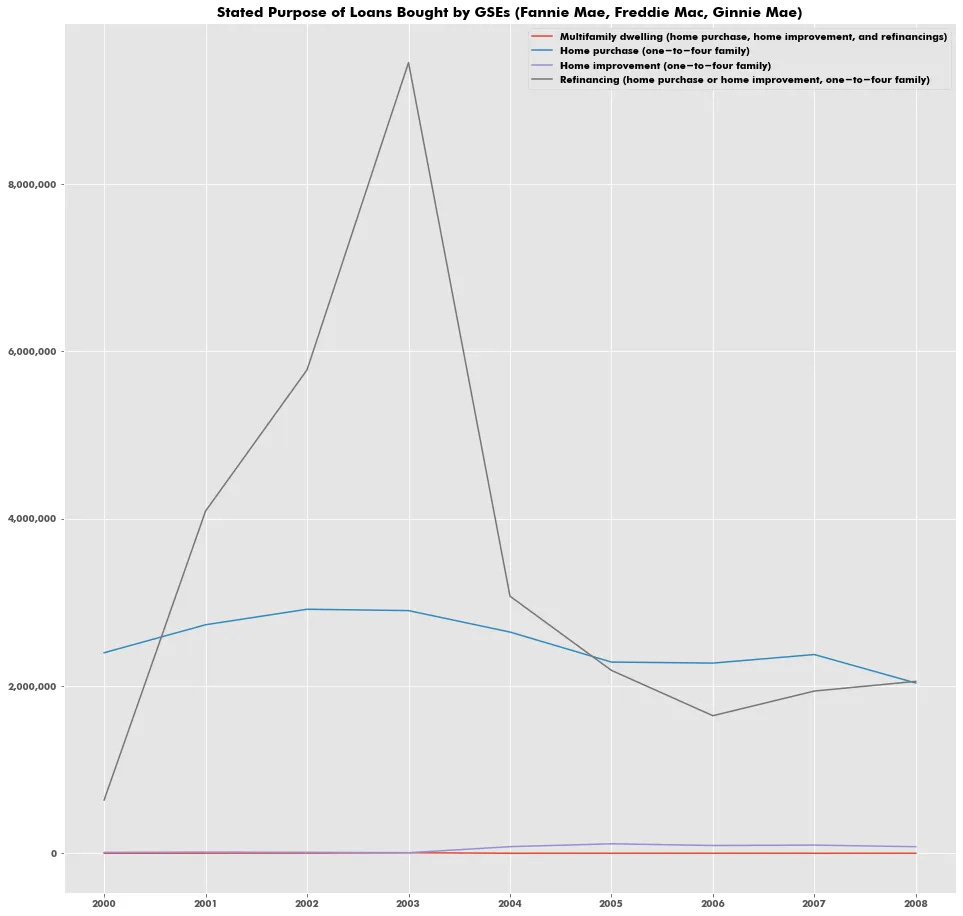

With the increase in interest rates, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac stopped buying as many mortgage-backed securities beginning in 2004.

When the crisis hit, CMBS disappeared entirely. While much scrutiny has been placed on subprime lending as the culprit, more recent research has shown the opposite as there was no discernible change in the average credit score during the subprime crisis.

Additionally, many of the failed loans, like Alt-A loans, were refinancing loans. They were referred to as “liar loans” for the low requirement on paperwork, but often times refinancing loans don’t require as much information as they already have loans on file.

One of the larger failures of the crisis, Indymac, leaned heavily on Alt-A loans. But while the California bank would get its rating downgraded and be the target of rumors of a liquidity crisis, its loans fared relatively well.

ACORN’s Role

Substantial blame for the widespread subprime lending at the time fell on the nonprofit organization Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN). By lobbying for lending standards that benefitted lower income individuals, they encouraged the bloated subprime market.

An undercover video produced by Project Veritas supposedly showed ACORN employees assisting someone hiding illegal activity to get government assistance. Following that Congress would start an investigation of ACORN’s activities.

But the investigation never showed any substantial evidence of falsified government applications. Instead, two reports from the House Oversight Committee would detail how ACORN regularly ran afoul of Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rules for nonprofits by blending its finances with affiliate organizations, running partisan political activities like electoral campaigns, falsifying voter registrations, and embezzlement. The reports document ACORN’s affiliation with the labor union SEIU as seamless, and documents revealed their heavy involvement of electing then Illinois Governor Rod Blagojevich among others.

ACORN was also heavily involved in lobbying on home lending laws, particularly the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). ACORN was regularly accused of fomenting the subprime crisis by supporting changes to CRA along with the Clinton administration in 1995. But the Financial Crisis Inquiry Report found no such connection:

The Commission concludes the CRA was not a significant factor in subprime lending or the crisis. Many subprime lenders were not subject to the CRA. Research indicates only 6% of high-cost loans—a proxy for subprime loans—had any connection to the law.

Yet ACORN was not involved in subprime lending. In fact, they regularly advocated against subprime lending and produced a study in 2006 showing its deleterious effects. Subprime loans and CRA loans are not equivalent, but they can overlap. Subprime loans are those with lower credit scores while CRA loans are those with lower income. Prior research showed that 67 percent of subprime borrowers were upper or middle income. CRA loans can also be risky, and some critics have pointed to high delinquency rates as high as 35 percent at a single bank with few of them not considered “subprime.” A National Bureau of Economic Research paper showed that CRA loans were 15 percent more like to be delinquent one year after origination.

The CRA stipulates that some amount of a bank’s lending should be directed to affordable housing in various ways—low interest rates and or low down payments. If banks didn’t adhere to the CRA, ACORN could sue and reap the benefits. Much of that money would be funneled into ACORN’s political activities by its affiliates. Between 1993 and 2008, ACORN received almost $40 million in funds from home lending banks such as Bank of America, J.P. Morgan, and Citigroup, but the list is widespread:

ABN/AMRO, Ameriquest, ASC Mortgage, Bank of America, Chase, CitiFinancial, CitiMortgage, Countrywide, Dovenmuehle Mortgage, EMC Mortgage, First American, GMAC, Green Tree Servicing, Homecomings Financial, HomeEq, Household/Beneficial, M&T Bank, National City, New Century, Ocwen Servicing, Option One, PHH/Cendant, Saxon Mortgage, Standard Mortgage, U.S. Bank, Wachovia, Washington Mutual, and Wells Fargo

Phil Gramm, author of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley act that enabled CDOs, was heavily critical of the CRA agreements that ACORN and other community groups entered into. He termed the practice of groups demanding cash payments and loan commitments in exchange for a good community investment rating under CRA “extortion.”

Good CRA ratings are necessary for banks to get approval for mergers. Ostensibly, CRA ratings exist to prevent abusive banks from growing larger. But there were questions to how effective even that was. OneWest—the Paulson-ba

cked bank that grew out of the failure of Indymac and was accused of being a foreclosure machine— passed CRA muster without much issue, allowing it to merge with the bank CIT Group.

In the years prior to the financial crisis, securitization of CRA loans ballooned, with investment firms like Bear Stearns offering CRA mortgage-backed securities and government entities like Fannie Mae buying them up.

Besides the bank settlements, ACORN was receiving millions in government grants. Details are scant as the organization doesn’t file a publicly available 990 form with the IRS. But reports detail the organization receiving $42 million from Housing and Urban Development (HUD) between 2000 to 2009. It had an annual operating budget of $28 million with ten percent coming from federal sources. A Government Accountability Office (GAO) report lists around $48.4 million in government grants between 2005-2009.

Yet with all the money in their coffers, it doesn’t appear as if ACORN did much in the way of housing support and foreclosure assistance—ostensibly its main objective and where most of its money came from.

Most of ACORN’s annual reports detail its efforts in community organizing and politics. Their 2006 annual report lists helping 1,234 homeowners refinance into more affordable mortgages. Their 2007 annual report doesn’t mention any metrics for homeowner assistance despite being in the middle of the foreclosure crisis.

Another document revealed by the Oversight Committee shows ACORN’s attempt to sell their California list of members. But the list has only a paltry 16,202 addresses.

In previous documents, ACORN boasted a paid membership role of over 400,000, bringing in almost $5 million a year. To get close to that, every other state would have to have the same number of members as California, the most populous state in the country, and most of them would have to be dues-paying members.

Great piece. Informative and well written.

The housing and stock markets are both in dire straits but for different reasons (I’m in Texas btw). Id love to hear your view of where we are heading next.