Estimating Retail Theft With CVS Filings

In December, the National Retail Foundation (NRF) walked back an estimate that said around $45 billion a year in retail losses were due to organized retail crime.

The estimate came from the 2021 Senate testimony of Brendan Dugan, director of organized retail crime and corporate investigations for CVS Health, and that estimate was based on a 2016 NRF survey stating that average shrink rate for retail—inventory loss due to damage, theft, or error—was 1.38 percent, and it costs the overall economy $45.2 billion a year.

That $45.2 billion estimate includes all causes of inventory loss, not just theft. But in other places NRF has estimated total theft around the $45 billion mark. For example, they put total shrink in 2022 at $100 billion. Based on other NRF estimates for percentage of shrink due to theft—shoplifting is 39.3 percent, employee theft is 35.8 percent—that would put the total loss from theft above the $45 billion mark.

The NRF estimates definitely seem high. The Retail Dive story that originally highlighted the NRF discrepancies admits there may not be a good estimate for retail theft.

For the pharmaceutical chain CVS, a shrink rate of 1.38 percent of its annual revenue from product sales for 2022 ($226.616 billion) would be $3.127 billion. If it was based off of the lower cost of products sold ($196.892 billion), it would still be a massive $2.7 billion.

In the testimony from Dugan, he put the estimate at a more reasonable $200 million in losses to organized retail crime per year, and the average thief steals “$2,000 in just 2 minutes.” While that is much smaller estimate—.09 percent of CVS’s annual sales revenue—it still might be massive considering that they mainly sell pharmaceutical drugs.

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings for CVS don’t always give estimates for retail theft. The one year numbers were provided was in 2023. Strangely enough, that year, both CVS Health and Walgreens listed “store damage and inventory loss insurance recovery” losses from the riots following the George Floyd protests of exactly the same amount—$40 million.

And that includes damage to the stores, not just inventory loss—far below the $200 million quoted by Dugan. And they list no recovery from inventory losses in prior years.

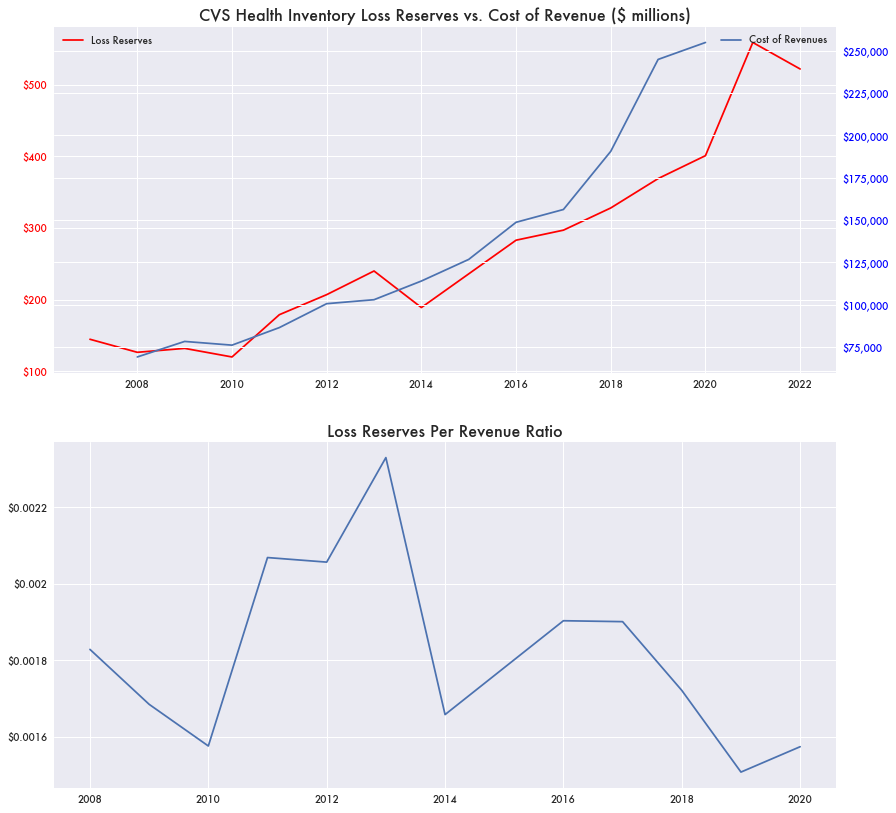

CVS filings do regularly detail how much they reserve for inventory losses. While that number floated around $132 million a year in 2009, since then those reserves have quadrupled. In 2022, reserves for inventory loss topped $559 million.

That increase is in line with CVS’s growth in operating costs, which have also quadrupled since 2009. Much of that appears to come from the cash paid for inventory, largely pharmaceuticals.

But it doesn’t say how much inventory loss there was or how much loss was covered by insurance if any. It could simply be an estimate based on a percentage of operating costs.

CVS’s large growth in operating costs don’t make a lot of sense either. Operating costs should ostensibly grow year over year with inflation, company growth, and various other business changes, like acquisitions, but they shouldn’t quadruple over that time.

CVS did add approximately 2,000 locations when it acquired Target’s pharmacy segment and the pharmacy services provider Omnicare. But 2,000 additional locations doesn’t equate to quadruple growth, and that largely occurred just in 2015, not continuously across 15 years.

Pharmaceuticals have been getting more expensive, but according to a 2022 report from Health and Human Services (HHS), from 2016 to 2021 total retail spending hasn’t gone up that much. For chain store pharmacies like CVS, total spending went from $161 billion to $167 billion, and it temporarily went down to $154 billion in 2017. When adjusted for inflation, average expenditures per prescription for retail pharmacies went down.

If CVS was losing millions in theft per year, most of that would likely be from theft of pharmaceuticals. Under the Controlled Substance Act, pharmacies are required to report all loss or theft of controlled substances to the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA).

Potentially related but not necessarily so, CVS is now moving out of the business of sales of more sensitive drugs. In 2023, CVS announced a number of changes following their settlement of opioid-related lawsuits that included phasing out of all sales of schedule 3, 4, and 5 drugs by the end of the year. Drugs affected by that change include:

Schedule III: Tylenol with codeine, ketamine, anabolic steroids, testosterone

Schedule IV: Xanax, Soma, Darvon, Darvocet, Valium, Ativan, Talwin, Ambien, Tramadol

Schedule V: Robitussin AC, Lomotil, Motofen, Lyrica, Parepectolin

Investigative Economics previously reported that major pharmaceutical chains like CVS, Walgreens, and Rite Aid accounted for a third of all opioid distributions based on data from 2006 to 2014.