Deinstitutionalization Came From Kennedy and Governor Reagan, Not President Reagan

Deinstitutionalization is the term for the major shift in treatment for mental illness away from large state psychiatric facilities and more towards outpatient treatment through local hospitals and other services.

It’s sometimes associated with the growth in homelessness, drug addiction, and mental health problems in urban centers beginning in the 1980s and continuing to this day.

Those with severe psychological issues, unable to hold a job, and find a home would no longer be housed in psychiatric facilities. Instead, they lived on the street and became addicted to drugs, although they still might receive health treatment in outpatient scenarios.

Estimates put the number of homeless with serious mental health issues at 21 percent, although other estimates have it as high as 80 percent. Cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, Portland, and Philadelphia now have large pockets of homeless camps connected to high opioid use and mental illness.

Various stories have detailed how President Reagan was responsible for deinstitutionalization in the 1980s by closing down facilities and turning away from community health centers.

While it’s true that the federal government changed funding for community health centers in the 1980s, abandoning a plan put in place by President Carter, deinstitutionalization was a long time in the making and actually started back in the 1960s under President Kennedy.

In general, the federal government has no authority over state-run institutions, but federal funding of Medicaid and Medicare encouraged alternatives to state-run facilities.

While Reagan avoided subsidizing community-based health treatment, the states still footed the bill by increasing their share by 1,528 percent from 1981 to 2015 according to a report from the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD).

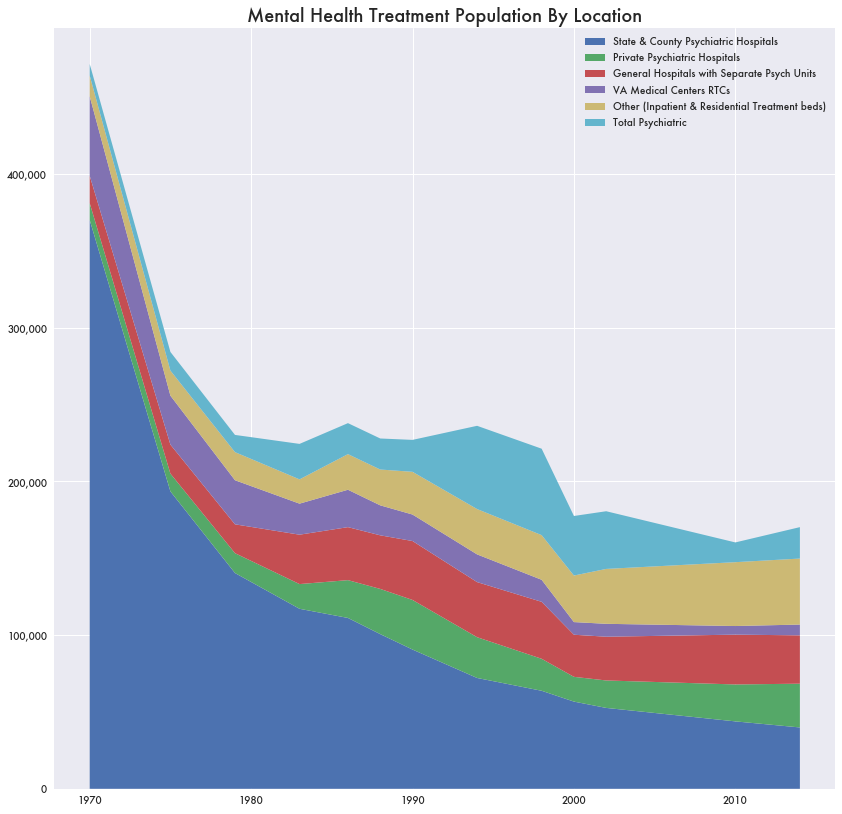

Combined with a focus on outpatient and in-home treatments and civil rights for the mentally ill, inpatient treatment for mental illness shrank considerably. By the time the 1980s rolled around deinstitutionalization was almost already complete, although it would continue slowly into the current day.

Yet Reagan may still be largely responsible for starting the process over a decade earlier. In 1967, Reagan as then-governor of California would sign into law the Lanterman–Petris–Short (LPS) Act which would prevent the state from forcibly institutionalizing the mentally ill against their will for various conditions, likely the first in a series of liberalization policy changes for mental illness.

While there were financial reasons to move away from large state psychiatric care for certain patients, there may not be any sign the states have saved any money in the process.

Moving Away From State Psychiatric Facilities

Based on NASMHPD data, between 1970 and 1983 the number of mentally ill housed in treatment would be cut in half—from 471,451 to 224,347. Those in state psychiatric facilities would drop by a third—from 369,969 to 117,084.

Civil Rights and Outpatient Treatment

Kennedy believed the mental health approach of large state-run institutions didn’t serve patients well, like his sister Rosemary Kennedy who received a lobotomy at one, and he pushed for more humane treatment through community health centers.

It also followed a general push for improved civil rights for the mentally disabled. There were legal decisions that would require a person to be a danger to themselves before being forcibly detained, such as Lake v. Cameron, O’Connor v. Donaldson, and Addington v. Texas. Other lawsuits defined mental illness as a disability covered by the Americans with Disabilities Act.

It wasn’t all based on a liberal approach to mental health. The introduction of Thorazine in 1954 allowed for informal treatment in outpatient settings. The advent of Medicare and Medicaid—which did not make payments to state hospitals in general—incentivized outpatient treatment at local hospitals and in-home treatment.

Large Elderly Population

A large portion of the mentally ill population were simply seniors with disorders like late-stage dementia. Removing state and federal subsidies simply forced them to live at home or at nursing homes. According to the NASMHPD paper, in 1970 those 65 and older were 29.3 percent of state and county psychiatric hospitals. By 2014, it was down to 8.8 percent.

But even after accounting for an elderly population that might now be treated at home, deinstitutionalization likely left many untreated and on the street.

Using the NASMHPD data and excluding the over-65 population, there would be 178,093 fewer housed patients between 1970 and 2014. That is assuming a fixed mentally ill population, which is unlikely considering population growth and demographic changes over time.

Possibly Not Saving Much

One beneficial aspect of deinstitutionalization was that it was supposed to save money for the states. With more funding coming from Medicare, Medicaid combined with at-home treatment and private care, state psychiatric hospitals were not needed as much and wouldn’t be as big a burden on their budgets. But that may not be true.

A report on California’s Department of Mental Hygiene from 1960, prior to deinstitutionalization, put the annual budget at $123,750,551. In 2024 dollars, it would be $1.3 billion.

But a report from National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors Research Institute in 2010 placed California’s state mental health agency (SMHA) budget at over $8 billion in 2024 dollars—over six times what it was in 1960.