Currency Policies Drove the 1987 Market C̵r̵a̵s̵h̵ Reset

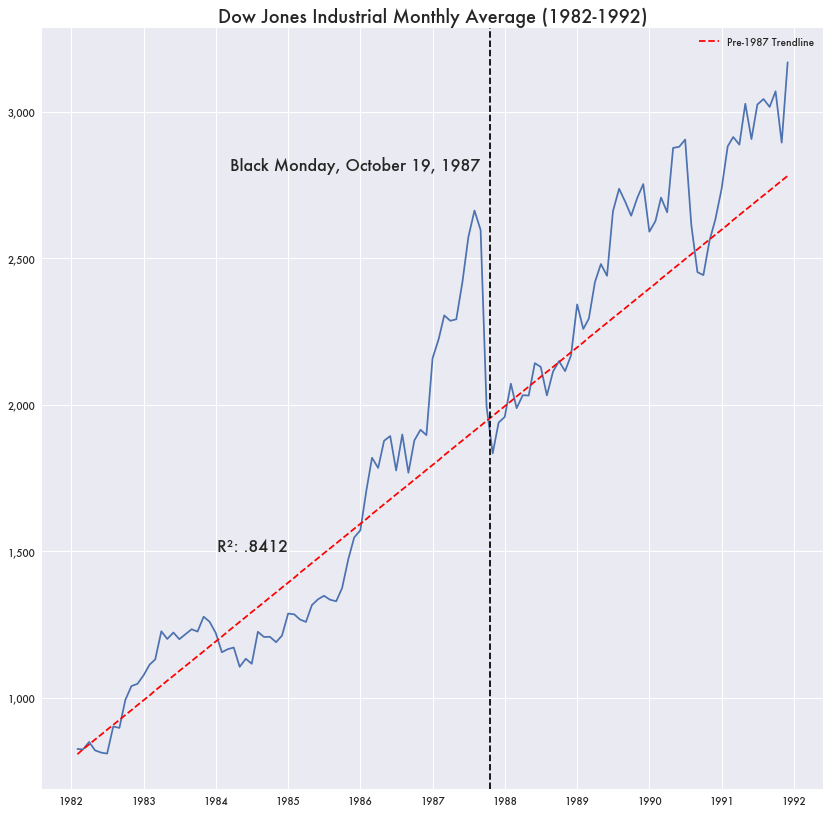

When the stock market crashed on October 19th of 1987, otherwise known as Black Monday, it was the largest market collapse since 1929. The Dow Jones monthly average lost over 600 points in a month. Over $1 trillion in value disappeared in a matter of weeks. It presaged an era of other larger market crashes like that of the dot-com crash of 2000 and the mortgage crisis of 2007.

But what’s odd about that crash is that the market ended up no worse for wear. Wall Street had been on a bull run since 1986, and the crash simply returned the Dow Jones average to around where it would have been if the bull run never existed.

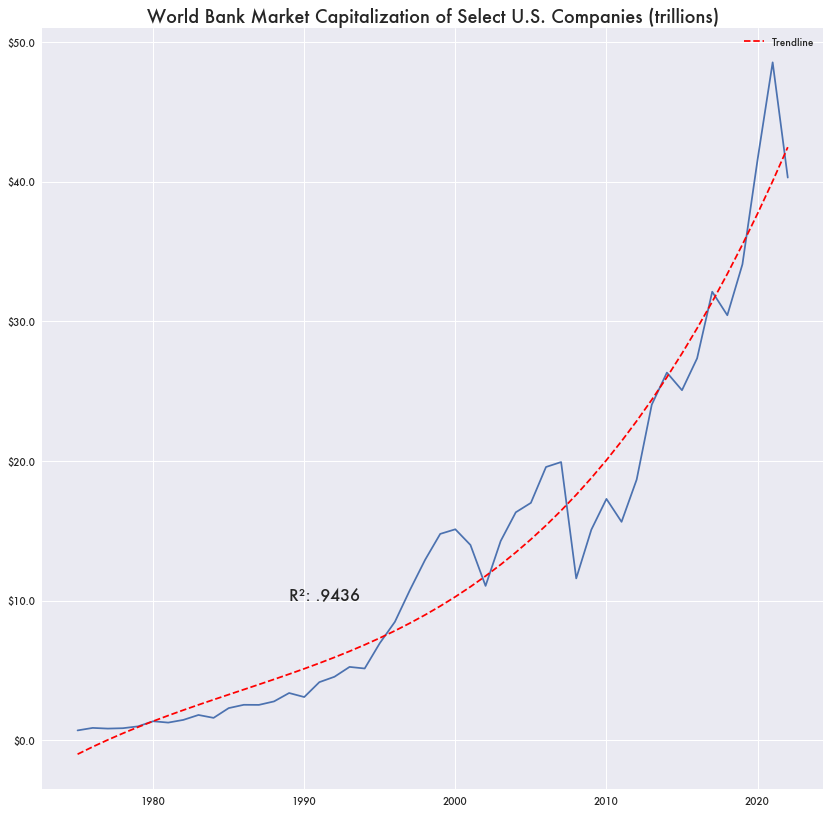

Additionally, neither the bull run leading up to the crash nor the crash itself had any real effect on market capitalization. Individual stock values were higher during the bull run but the overall market value—stock value times stock volume—hadn’t budged.

A Government Accountability Office (GAO) analysis of the events ascribed the crash to a bill put before congress that would eliminate tax breaks for corporate mergers and acquisitions, which would have severely curtailed takeovers ostensibly a driver of the bull run. The bill was never passed, but it may have simply spooked the market.

But currency changes appear as the likely driver of the bull market leading up to the crash, particularly the Plaza Accord in 1985—a financial agreement between France, Germany, Japan, United Kingdom, and the U.S. that involved devaluing of the U.S. dollar.

According to an National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) report, prior to 1985 the strength of the U.S. dollar was driving a large trade deficit. To counteract this and avoid trade restrictions, the U.S. coordinated with five of the largest industrialized countries to devalue the dollar in what would be the largest currency policy effect since Nixon moved the U.S. off of the gold standard.

While the Accord helped coordinate currency changes without conflict, devaluation of the dollar started in February of that year as James Baker took over as Treasury Secretary after the inauguration of Reagan’s second administration and following various other international meetings of the G-5. Previously Don Regan held the post of Treasury Secretary overseeing the dollar’s ascent.

While the U.S. started devaluing the dollar in January, the stock market didn’t start its bull run until after the Plaza Accord in September of that year.

Between the change in currency policy in 1985 and Black Monday the dollar would lose almost half its trade-weighted value in two years. The decline would continue through most of 1987, despite the Louvre Accord in February of that year—a similar meeting of G-5 nations in Paris, this time to halt the devaluing of the U.S. dollar.

While the Louvre Accord couldn’t stop the dollar’s decline, the decline came to halt by the end of 1987, a couple months after Black Monday.

A cheapening dollar would ostensibly drive mergers and acquisitions as it makes buying a majority position in a stock more affordable. A bull run in cheap stocks such as penny stocks could drive the Dow Jones Average without making much of a dent in the total market capitalization.