Corzine Bet on Sovereign Debt Even as European Economy Was in Freefall

Jon Corzine is the ex-Goldman Sachs executive who went on to be Governor of New Jersey and a bundler for President Obama’s campaign runs, only to move back into finance and take the helm of a commodity trading firm, MF Global.

MF Global would then collapse into one of the largest U.S. bankruptcies in history as the company under Corzine’s direction bet heavily on sovereign debt using in-house lending, otherwise known as a prop bet, despite it not being any way related to the commodity trading that the company was known for.

The dates when the investments were made are not exactly known, but it was detailed as transpiring not long after Corzine took control in March of 2010.

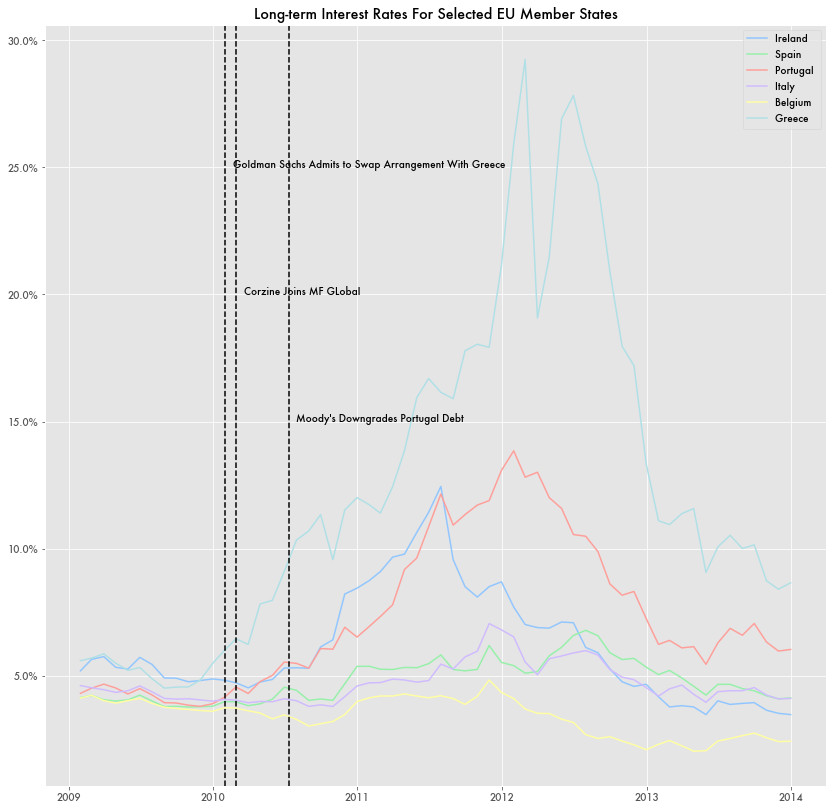

Yet not long before then, Greece’s economy was already in freefall, and it was Corzine’s ex-employer, Goldman Sachs, that would admit in February of 2010 to helping the country hide its true total debt through complex swaps agreements.

Part of the swaps arrangement that was made in 2001 involved assuming a currency exchange rate that was not accurate at the time. Goldman Sachs defended the deal as something that had been done before for other European countries’ sovereign debt and that it was necessary for Greece’s entrance into the Eurozone. The swaps hid an additional 2.3 billion to Greece’s already substantial debt.

While Corzine did not invest in Greek debt, he bet on a host of other European countries that were mired in the debt crisis that followed Greece—Spain, Portugal, and Ireland. While they did not default, Corzine also bet on Italy and Belgium, but effectively all of Europe was hit by the debt crisis. Liquidity was at a standstill following the financial crisis and various housing bubbles, and many countries would lean on the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for bailouts.

Portugal’s economy had been in economic stagnation for the better part of the last decade, and Moody’s would downgrade the country’s debt in July, only a couple months after Corzine made his gamble. Ireland had been struggling with finances for years and instituted numerous credit solutions to patch up the problems such as the Credit Institutions Scheme in 2009. Spain had been in a recession for years at that point and their debt to GDP ratio had almost doubled in three years by the time Corzine was making his bet.

Heavily Leveraged In-House Borrowing

In the same way that Greece used swaps to hide the debt, Corzine borrowed money from MF Global in a way that would hide the debt for months and even show a profit for a time.

Not only was it a large bet on European debt, but it was heavily leveraged—a large amount borrowed based on few assets. Estimates put the ratio of money borrowed to assets at 80 to 1. It would be a high risk even if the investment itself wasn’t also risky.

Such in-house borrowing is no longer allowed, and the CFTC was working on legislation to prevent it before MF Global collapsed, but Corzine himself actively lobbied the agency to postpone the rule. The rule was eventually instated in December of 2011.

Corzine might have known MF Global would be able to make such a bet without alarm bells ringing because of other failed bets in recent years. Only four months before Corzine joined the company, MF Global was sanctioned by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) for lack of oversight in allowing a trader to run up losses of $141 million.

With a large debt hole on its balance sheet, MF Global would eventually fall into bankruptcy. At one point, customer assets would be used to try and plug the hole. While there is some uncertainty about who did what, Corzine would eventually testify before Congress on the affair and settle a $5 million civil suit. He would also be banned from working in the futures industry.

Following the company’s collapse, the international investor George Soros would buy up the European bonds that tanked MF Global’s balance sheet at a considerable discount. According to a Reuters report, a substantial portion of MF Global’s assets would be sold to none other than Goldman Sachs.