Autism Epidemic Exploded As Diagnostic Standards Changed

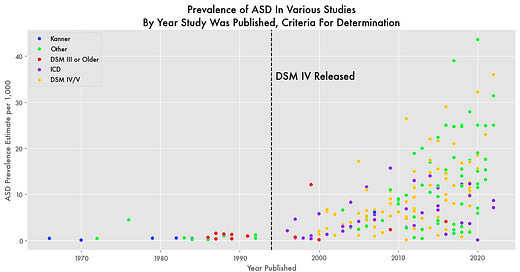

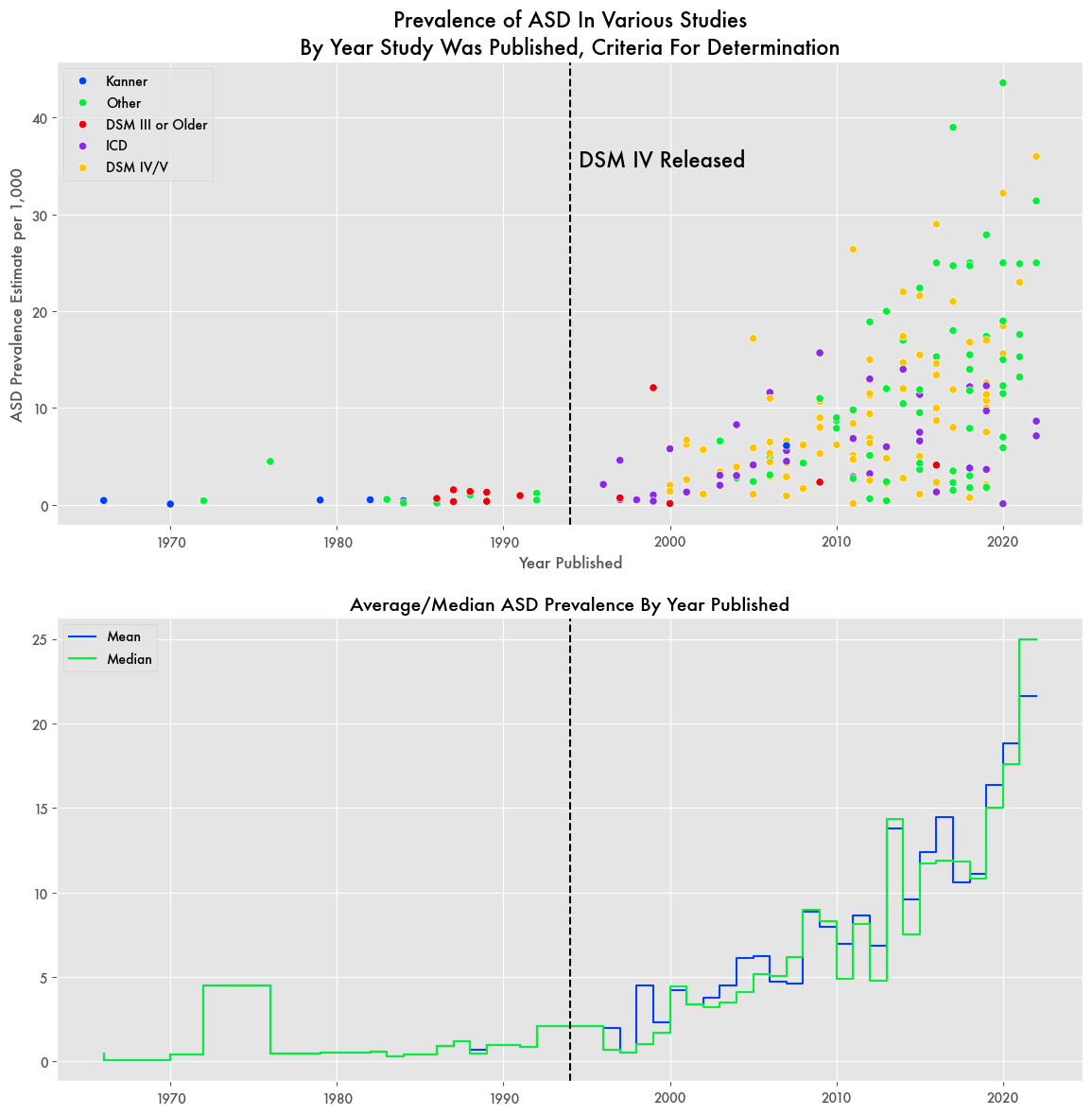

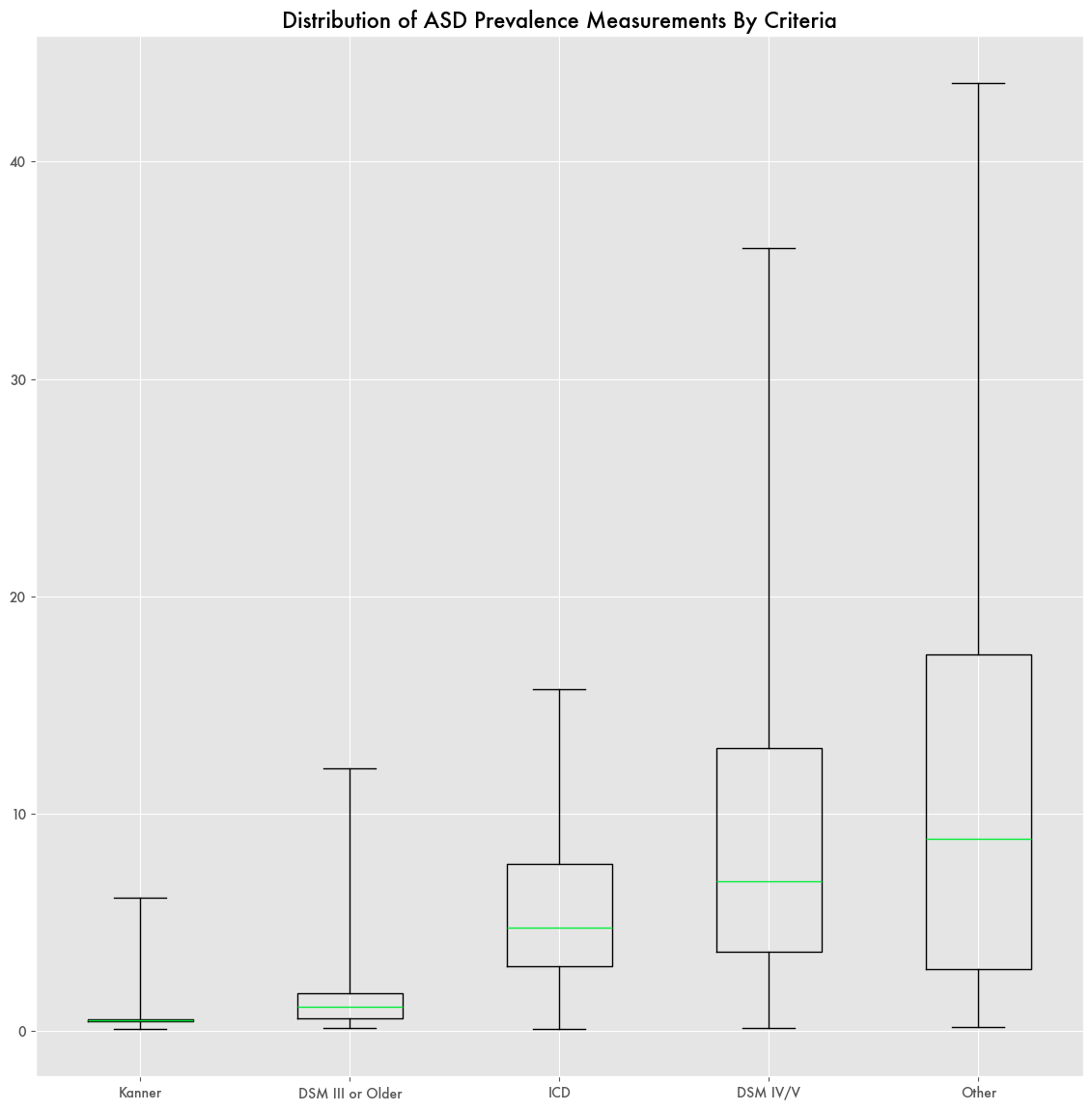

In the 20th century, autism was considered a rare condition, but it became increasingly common over the last three decades. Studies of children in the 1960s through the 1990s consistently showed a prevalence rate for autism of less than 1 child per 500, but current studies now show it diagnosed at around 1 in every 36 children—a 13-fold increase.

The possibility of an autism epidemic led to the oft-debated theory of vaccines as the source. Ostensibly, more children were getting more and more injections at an earlier age, particularly those with mercury preservatives, leading to neurological conditions like autism as a result.

But the vaccine-autism link has been regularly dismissed. The one major paper that connected the two was retracted, and mercury is rarely used as a vaccine preservative anymore. Yet the question about the autism epidemic remains open.

Robert Kennedy Jr., head of Health and Human Services (HHS), has made autism a focus of his tenure, promising to find the cause of it by September of 2025 and calling it preventable and worse than COVID.

But part of difficulty of untying the causes of autism will most certainly involve re-establishing the definition of what autism actually is.

What might be referred to as the autism epidemic started in the late nineties right after the World Health Organization (WHO) updated its standards for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) in 1992. The WHO’s ICD-10 would included other autism-like diseases including Asperger’s syndrome, Rett’s disorder, and childhood disintegrative disorder.

The publishing of the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV) in 1994 would also include Asperger’s. The DSM is effectively the bible of psychology in that it establishes the definition of disorders and how they are evaluated.

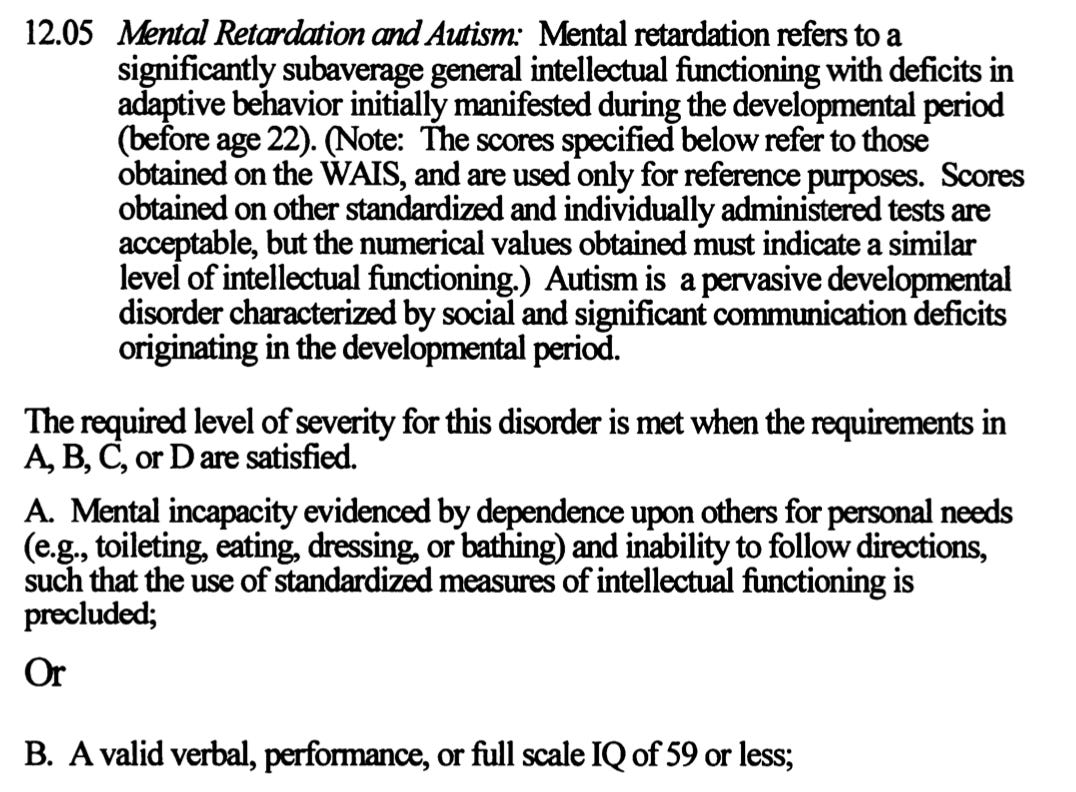

Then in 1997, the Social Security Administration (SSA) would redefine autism in its Disability Evaluation Under Social Security guidelines. Otherwise known as the Blue Book, it establishes the criteria for disabilities paid for under Social Security, either as a working adult or as a relative of someone covered by Social Security.

Those changes would eliminate standards for IQ in determining autism. Previously the definition for autism overlapped with that of other conditions historically referred to as mental retardation that required a maximum IQ of 70 to be eligible.

While there may have been reasonable cause to rearrange definitions, the end result has been to mix conditions with very disparate markers. For example, original autism was associated with low IQs, but Asperger’s is commonly associated with high intellectual ability.

Studies based on the newer definition of ASD would show much higher rates that kept climbing through the 2000s to today, not just the U.S. but globally as studies in Japan, Australia, and Europe all would show similar results according to compiled study data from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

Autism Data Still a Mess

While the confluence of autistic symptoms into the autism spectrum diagnosis might explain the growth in prevalence, there are still open questions about how much is due to Asperger’s or other sub-causes, where it is most prolific, and what could be potential genetic or environmental causes.

Data on autism in the U.S. is fraught with large discrepancies. Different data sets tell completely different stories about which demographics in which states and with which environmental factors correlate with larger prevalence of autistic symptoms.