Antarctica Has Not Seen the Same Temperature Increase, Sea Ice Decline As the Arctic

Over the past several decades, the Arctic has seen consistent warming linked to the decline in Arctic sea ice. The years 2020 and 2019 had the second and third lowest measurements of sea ice extent on record based on analysis from Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA).

But Antarctica has not seen the same kind of decline over decades. From 1980 to 2013 total area of Antarctic ice was actually growing steadily based on data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) through a collaboration with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

While sea has been increasing since 1980, since 2013 there has been a sharp decline in sea ice in a pattern unlike anything seen in the Arctic following increased volcanic and earthquake activity.

Earthquakes and Volcanos

According to a story on LiveScience, Antartica has seen the “strongest earthquake activity ever recorded in the region” in recent years. That seismic activity has come as both earthquakes and volcanoes.

In 2013 a smoldering volcano was discovered under Western Antarctica, which was anticipated to lead to an increased loss of sea ice based on research from the Washington University of Saint Louis. In late 2020, two 5.9 earthquakes hit the last continent that were attributed to magma seeping into the tectonic crust.

Little Change in Temperature

Similarly, Antartica has not seen the same steady growth in atmospheric temperatures as the Arctic. Based on data from NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory (GML), average annual temperatures at the South Pole through 2013 were effectively flat.

After 2013, temperatures have trended higher, with 2022 seeing an average annual temperature of -43 celsius, the second hottest temperature on record.

But even with the recent temperature swings, five out of twelve months have seen declining temperatures—unlike the consistent growth in temperatures seen in the Arctic.

Depends Who You Ask

A paper in Nature Climate Change with the title “Record warming at the South Pole during the past three decades” shows similar data for surface temperature—only increasing in the last decade. But it also shows a separate graph with steady growth in temperature since the mid-1970s.

According to the article, not only is Antarctica getting warmer over decades, “West Antarctica and the Antarctic Peninsula warmed more than twice as fast as the global average.”

That research is based on data from the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research's (SCAR) REference Antarctic Data for Environmental Research (READER) project data.

While that project has the goal of “creating a high quality, long-term dataset of mean surface and upper air meteorological measurements from in-situ Antarctic observing systems,” by combining measurements from reporting stations in and around Antarctica, the data is spotty and it doesn’t appear to show a multi-decade, smooth increase in temperature as described in the article.

Data for certain years and months is missing, and some of it had to be revised. For example, the station with the most reported data, at Grytviken in the South Sandwich Islands, is missing most data between 1980 and 2000. For the other years where there is data, it is missing 14 percent of its monthly data—making annual averages difficult.

While the data that is there shows an overall increase in temperature, it is only from the last 20 years, similar to that of NOAA’s data—not a century-long gradual increase similar to the Arctic. Between 1905 and 1980, average monthly temperatures barely budged with some declining slightly.

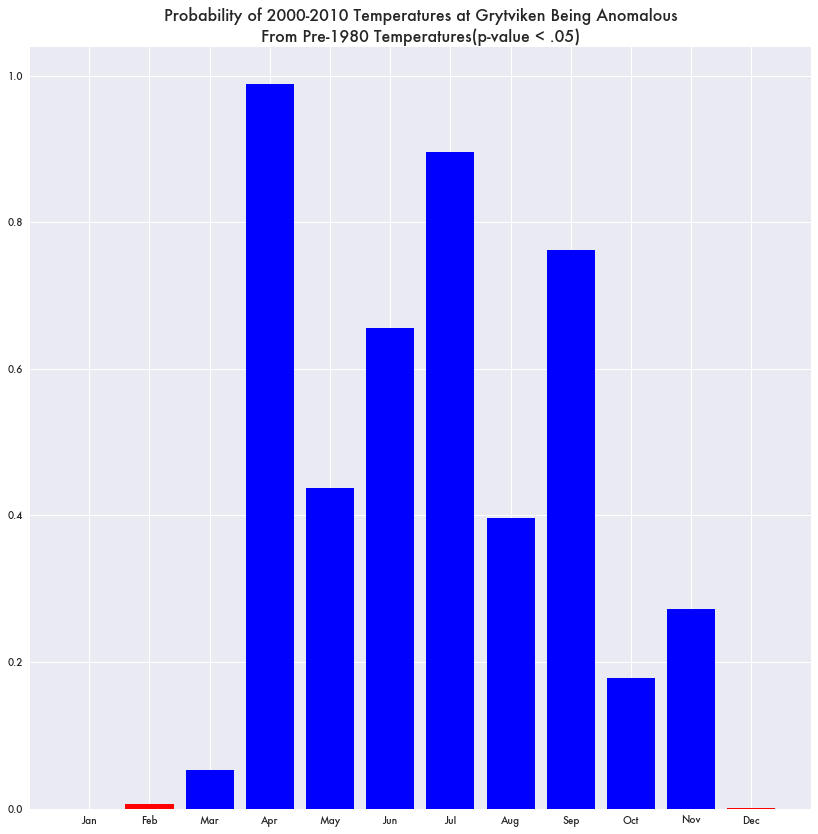

While there was some increase in temperature between 2000 and 2020, it wasn’t particularly anomalous from the pre-1980 data. Only three months—January, February, and December—had temperatures that were unlikely to be outside the norm of prior temperatures based on t-tests (p < .05).

Another article in Nature’s Climate and Atmospheric Science journal details a polar opposite view:

The Antarctic continent has not warmed in the last seven decades, despite a monotonic increase in the atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases.

According to the publication, while a portion of the western continent has warmed above average, the rest of it has only gotten colder.