2011 Drought Led to Largest Crop Insurance Payout, Particularly for Texas Cotton

Ten years ago, prices for commodities like corn, wheat, rice, soybeans and cotton spiked three years after the last price spike around 2008.

A confluence of events including droughts in Russia, Argentina, East Africa, the U.S., and China as well as heavy rains in Australia and Europe, a cold freeze in Mexico, and subsequent trade restrictions would lead to substantially higher prices, but also historically high futures prices according to a report from the USDA. Another source, ETF.com, would attribute the spike to a freeze in China, floods in Pakistan, and a ban on exports in India.

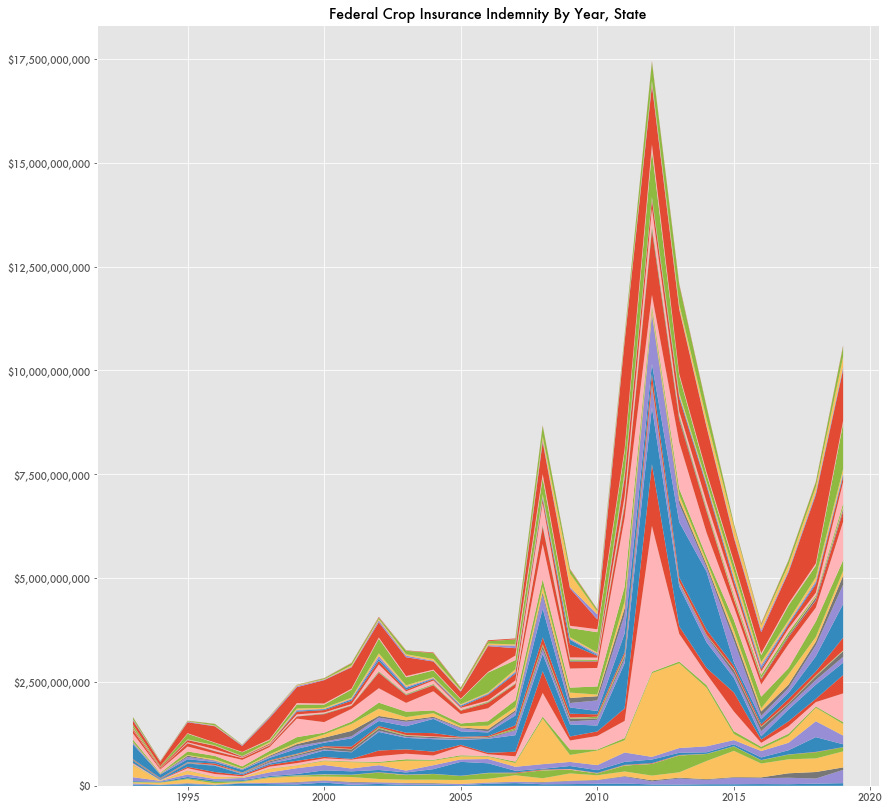

High prices and low yields in the southeast would also cause the federal crop insurance program to make the largest indemnity payout in history, mainly to Texas and Oklahoma, and mainly for two crops: corn and cotton.

While corn would have the largest total losses, they would be spread across numerous states. Kansas had the largest corn insurance payout, and it was less than half a billion. It was cotton in Texas that would be the single largest indemnified loss by state and crop.

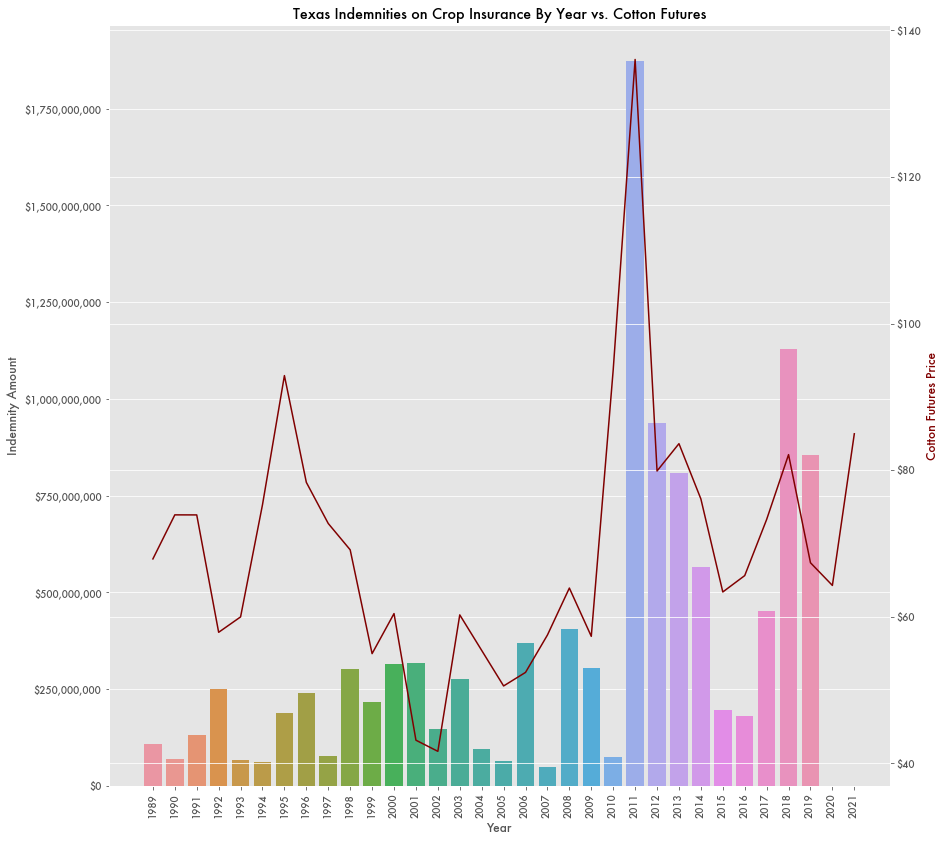

Over $1.8 billion alone would be paid to Texas farmers in 2011 for failed cotton harvests according to data from the USDA’s Economic Research Service Risk Management data. That represented 17 percent of all crop insurance payouts that year. As a result, net losses on crop insurance for Texas cotton farmers—indemnities paid minus premiums collected—over the last three decades would be over $2 billion.

Right next door, Oklahoma would see losses related to cotton three times larger than the amount paid in to insurance, although Oklahoma had a much smaller insured crop total.

Through the USDA, the federal government provides subsidized crop insurance through the Federal Crop Insurance Act. The Federal Crop Insurance Corporation reinsures the insurance companies that provide coverage by absorbing some of the losses of the program when indemnities exceed total premiums. The vast majority of insurance covers the four main crops: corn, wheat, soybeans, and cotton.

Insurance Claims and Futures Markets

Around the drought and price spikes, insurance payouts related to cotton would exactly follow futures indexes. As international prices spiked, rather than domestic production cashing in on the increased demand and larger payout, domestic droughts impeded farmers ability to cash in on the bull market in commodities.

Insurance premiums and payouts are calculated based on futures prices and other factors according to the CFTC. So a spike in futures prices would mean larger payouts per acre of failed crops.

Additionally, before 2014 cotton farmers received subsidies, such as direct and counter-cyclical payments—payments to compensate farmers between the price they earned for their crop and expected values—from the USDA that could sometimes account for 50 percent of the value of the crop. From 2005 to 2008, those counter-cyclical and direct subsidies for cotton could account for about $1.5 billion a year.

Subsidies helped domestic producers compete with growing production in places like China. But a trade dispute brought by Brazil in 2002 against these subsidies would eventually be settled in 2009. Counter-cyclical payments would be eliminated by 2009, and the 2014 Farm Bill ended direct payments.

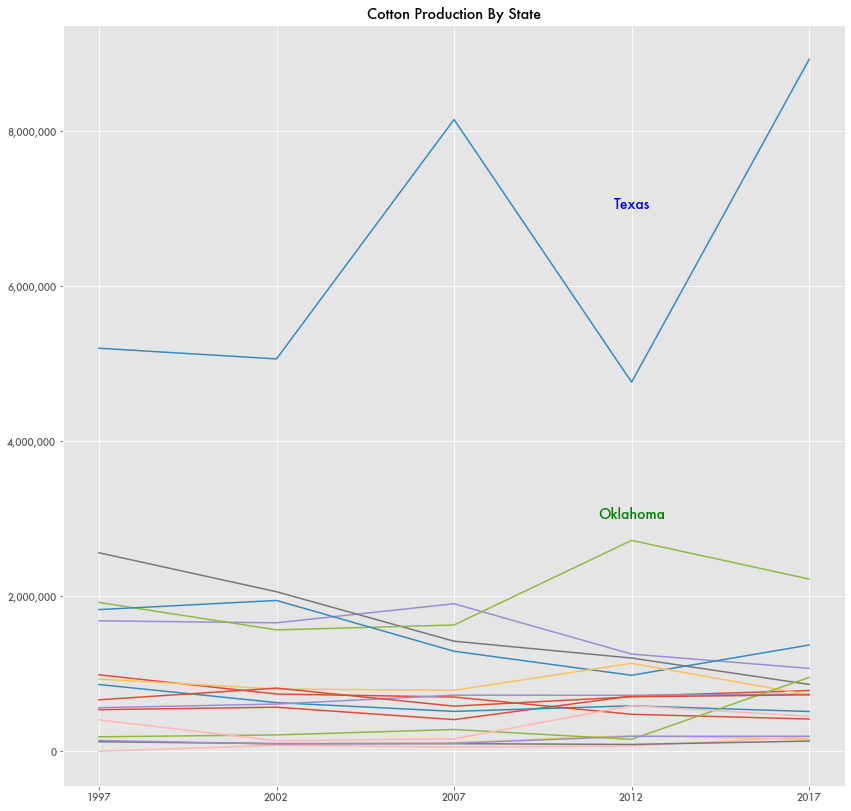

Since then, cotton production has only grown in the locations hit hardest—Texas and Oklahoma—despite their arid conditions not being ideal for cotton farming. Oklahoma cotton production would increase 6-fold from 2012 to 2017 according to certain USDA data.

Cotton farming has languished in more humid locations such as the southeast where the crop has historically grown.